Origins of Hastings

The word 'Hastings' comes from the 'Haestingas', the people who supported a Saxon (Danish or German) migrant leader called Haest (or Haesta) who occupied Sussex east of the Pevensey Levels in the 6th or 7th century. In Old English, -ingas means followers, so originally the word 'Haestingas' was describing a group of people spread over a wide geographic area, rather than giving a name to a village or a town.

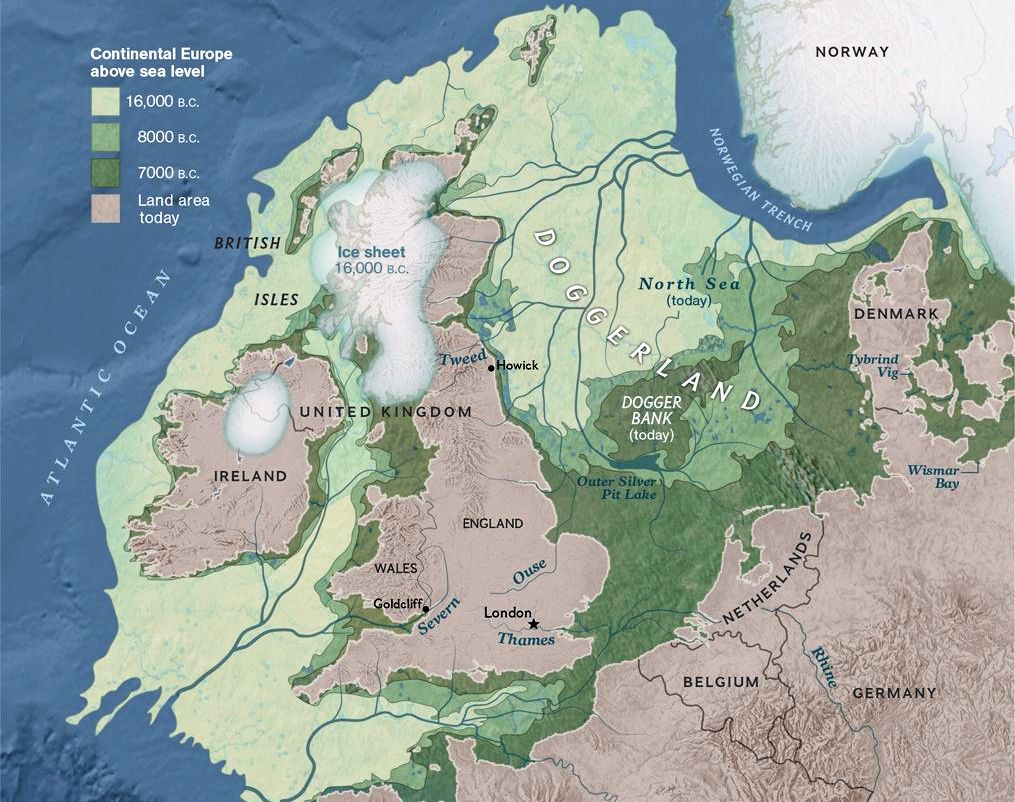

There had been some people living in what is now eastern Sussex for thousands of years before the Haestingas, except in the Ice Ages. The most recent Ice Age reached its height c19,000 BC, making England almost uninhabitable. There were then glaciers north of a line between the Severn and the Wash, and tundra to the south of it. The gradual retreat of the ice northwards over the next 10,000 years brought itinerant hunter-gatherers across the land-bridge from the continent until about 9,500 BC, when southern England started becoming a place where people could again live permanently. The Ice Age had ended by c8,500 BC, and this was followed by a steady global warming between roughly 7,000 BC and 3,000 BC, by when it was hotter than today. Southern England became a near-forest of mainly deciduous trees, with many forms of animal and plant life.

During the last Ice Age England was part of the Europe land-mass. There was a valley where the English Channel is today, but the sea level was much lower at that time, and the only significant area of water in the valley was a wide river, a continuation of the River Rhine draining much of northern Europe into the Atlantic. Then, as the ice melted, the water level rose in the North Sea until, around 6,150 BC, there was a huge landslip on the Norwegian coast. This caused a tsunami to break through the bridge-cum-barrier of the North Downs at Dover, cutting Britain's connection to the European continent, and creating the Channel, much as we know it today.

The Europe that was.

So Britain only became a sea-bound island about 8,000 years ago. It took another 3,000 years, to about 3,000 BC, for the British Isles to take a shape similar to that of today. The sea level continued rising till about 1,000 BC, since when the many changes in the coastline have been more the result of shingle movement, steady erosion and severe storms.

There is archaeological evidence of continuing human life in the Hastings area since the end of the last Ice Age c8,500 BC. The period from then until c4,000 BC is known as the Mesolithic period (Middle Stone Age), with a continuation of the semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer-fisher ways of life, using flint to arm arrows, javelins and fishing spears. The largely forested Hastings area was heavily populated in Mesolithic times, as was shown by the discovery of nearly half a million worked flints during excavations on the Hastings-Bexhill Link Road. There was an important Mesolithic settlement on the West Hill, where Ladies Parlour and the Castle are today.

The Mesolithic period gradually evolved into the Neolithic period (New Stone Age) from c4,000-2,450 BC. Farming people arrived from Europe, bringing domestic plants, animals and some pottery. Communities became more settled and agriculture was developed to support the growing population. They built long barrows (burial mounds) for the remains of the dead, causewayed enclosures, and circles such as Stonehenge. Neolithic stone axes were found at Fairlight, plus flints in the Bourne Valley, and pottery on the site of the East Hill's cliff railway station.

A Neolithic flint-made cutting tool found at Fairlight.

Around 2,450 BC and over the next few centuries most of the existing population of Britain was rapidly displaced by a highly popular cultural phenomenon, known today as the Bell Beaker complex. This was a wave of immigrants whose ancestry lay in central Europe and further east to the Steppes. These lighter-skinned people were our forebears. They brought the use of metals, new customs, new burial practices and beautiful distinctive bell-shaped pottery. There was at that time a Europe-wide network of communities with vibrant links, shared beliefs and a sophisticated artistic culture.

The new use of metal by the Beaker folk gave the period from about 2,450 BC up to 700 BC the title of the Bronze Age. Bronze, a mix of copper and tin, had replaced flint for most tools by c1,400 BC. This was a period of great social and technological change, when people took the giant step from the Stone Age to the Iron Age. Bronze was brought from mainland Europe via southwest England, where there were good deposits of copper and tin. Three bronze axes from this time were found at West Marina in 1869.

In the Bronze Age the coastline was further to the south than today, and much more uneven, with many inlets. Pottery sherds were found in Ecclesbourne Glen. Trees dating to 1,500 BC and earlier can be seen along much of the low water mark between Pett level and Bexhill, showing the sea level was much lower then.

A tree from about 1,500BC at Pett Level.

At that time there was much interaction between the coastal communities of what are now England and France, sharing the same culture, and showing that the Channel was a means of communication, and not a national barrier, as it is today. Large wooden boats are known to have traded with France from Dover, and this probably also happened from the Hastings area. In 1992 a large part of what is believed to be the world's oldest-known sea-going boat were unearthed during town centre road works in Dover. The high-quality boat, now in Dover Museum, dates from about 1,550 BC.

The Middle to Late Bronze Age was a time when settled farming communities expanded across southern Britain, and extensive trade routes developed to allow the movement of metal ores for the production of bronze. These new networks linked wide-ranging regions across Europe, wuth considerable numbers of people moving.

The Iron Age is the name given to the period from the end of the Bronze Age at around 700 BC, until the Roman Conquest of Britain in 43 AD. As the name suggests, the period was characterised by the gradual introduction of iron as the most popular metal, as it was much harder and more useful than bronze for making tools, farming equipment and weapons. Sussex, particularly towards the end of the Iron Age and during the Roman period, was to play a particularly important role as a major source of iron ore from which iron could be smelted.

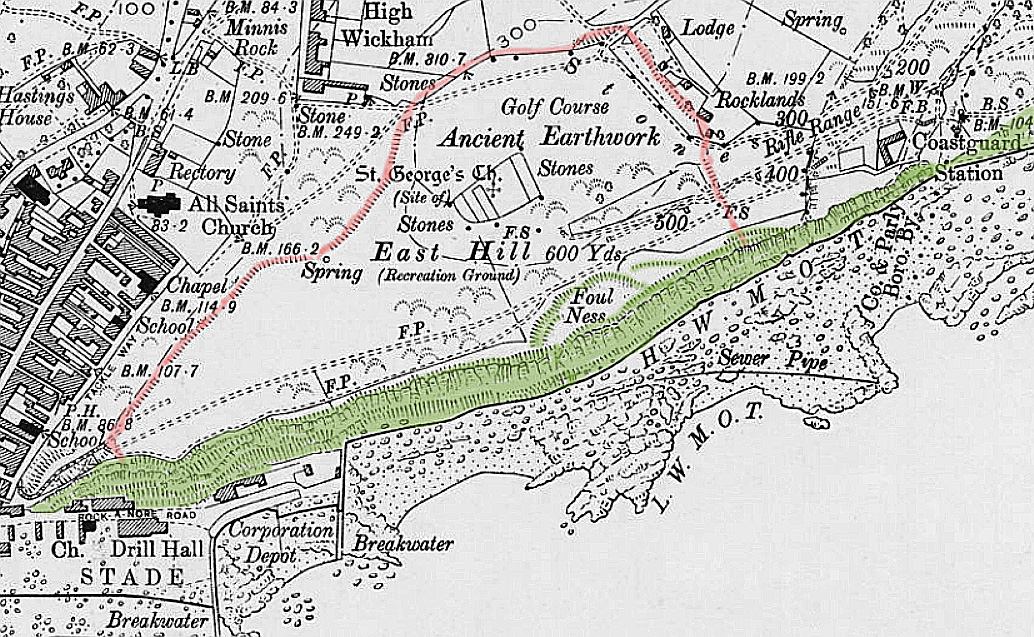

There were very wet and cold conditions during the Early Iron Age, but the climate improved significantly from c400 BC. This made the run-up to the Roman invasion in 43 AD a dynamic time, with more human activity, including the nucleation of settlement and the expansion of agriculture onto previously marginal land. By the last years of the Iron Age, Britain had between 1.5 million and 2.5 million people, living as farmers or small tribal groups, but with safeguarded areas (known as ‘Iron Age hillforts’) where they could meet for protective, cultural and religious reasons. The East Hills had such a hillfort, covering 60 acres, and possibly dating from the later Iron Age. Pre-Roman coins dating from 52 BC onwards were found in the Bourne Valley.

The Iron Age fort on the East Hill, inside the red line, drawn on an 1897 Ordnance Survey map.

When the Romans invaded England they may have experienced little conflict in Kent and Sussex, as indigenous traders had had a working cross-Channel relationship with them for many years. It appears that the Romans allowed the existing way of life to continue where possible, in a period which saw the reorganisation and expansion of settlement across Sussex. Their main interest in this area was the well-established iron industry, and it is likely that a coastal Roman settlement grew around this trade, although there is no archaeological evidence of an actual town.

However, there was a high-quality bath-house complex at the major Roman ironworks which was set up in Beauport Park just north of Hastings to produce the hardware needed by their military forces. This was the third largest ironworks in the Roman empire. In addition in the area around Hastings there were many dispersed settlements (eg, farms) which were probably involved in the iron industry.

Many Roman artefacts have also been discovered in Hastings itself, including a large quantity of coins in Elphinstone Road, and these indicate that there probably was a settlement and trading centre here, but it has been lost to the sea, or submerged below ground. Roman roads in the Weald were small and rough, and the iron would have been transported from Beauport by boats as much as possible. The large inlet of the Priory Valley, where Hastings town centre is today, would probably have provided a good harbour, with a wharf and/or a flat gravel spread where vessels could be beached at high tide and unloaded when the tide was out.

On top of the East Hill is an enclosure which for many years was called 'St George's Churchyard', but there is no evidence that there was a church on the hill at any time, and the soil-depth is too shallow for graves. There is some evidence, however, that the enclosure may have been a Roman signal station, for in 1840 an old earthen vase containing about 30 Roman coins was found inside the enclosure, and in a 1750 map the enclosure is named 'Beacon Hill' and there is a flagstaff with a red pennant in the south-east corner.

The possible Roman signal station (the compound) on the East Hill, in 1931.

After the Romans left Britain in 410 AD the population of England fell, and the indigenous people probably returned to much of their previous culture, living in self-sufficient rural settlements. In the following two centuries, Saxons and other native peoples of north Germany and Denmark area migrated into south-east England in what have been called ‘invasions’. But this may have been a largely peaceful influx by a relatively small number (tens of thousands?) of influential people who brought with them a new way of life, especially to thinly-populated areas such as eastern Sussex. Indigenous skeletons in graves dating from that time show no sign of having been killed in fighting, and there are no remains of burnt farmhouses.

It was the arrival of the prominent immigrant named Haest or Haesta and his/her backers in the 7th century which seems to have given a specific identity to the district lying between roughly the Pevensey Levels to the west, and Kent to the east and north. This settlement by Haest/Haesta probably brought a significant number of new people who shared common interests to this diffuse, sparsely habited and unnamed district. They may have been Christians before they arrived, because there are no pagan Saxon sites in the Hastings area. In 1856 an archaeological dig took place at what was believed to be a Saxon graveyard on the edge of the cliff on the East hill, where the Lift station is today.

A skull found in the 1856 dig.

Until 1066, the Haestingas were a ‘third county’, separate from Sussex west of Pevensey, and from Kent, with a stronger Hastings+Kent relationship than Hastings+Sussex. The earliest Haestingas seem to have lived in mainly farming groups initially. But in the 8th and 9th centuries England began taking shape as a single nation, and the Haestingas were forced to become part of it in 771 when King Offa of Mercia invaded and took control of the area. The 771 invasion by Offa is the first record of the name Haestingas.

Hastings had become some form of town by the end of the 9th century because it was one of the 31 fortresses - called burhs - founded in 878-79 by King Alfred as a defence against a Viking incursion of southern England. Hastings (called 'Haestingaceastre' as a burh) was one three burhs in eastern Sussex, the others being at Lewes and at 'Eorpeburnan', whose identity is unknown but was somewhere to the east of Hastings, possibly Rye.

But Hastings quickly became more than a fortress, because by c900 a new national economy was beginning to emerge, with more trading, manufacturing, transport and commercialised agriculture. It was then that the size of England’s population began to rise again, and towns began to develop for the first time since the Roman period. The main form of transport in England was by water, using natural havens and estuaries as harbours, and the lucky Haestingas could provide one of the nearest ports of passage to and from the continent for the budding cross-Channel trade. By around 930 Hastings had a mint, showing it was a significant town. The first recorded coins date from 985-91, and thereafter coins continued to be minted at Hastings until 1154.

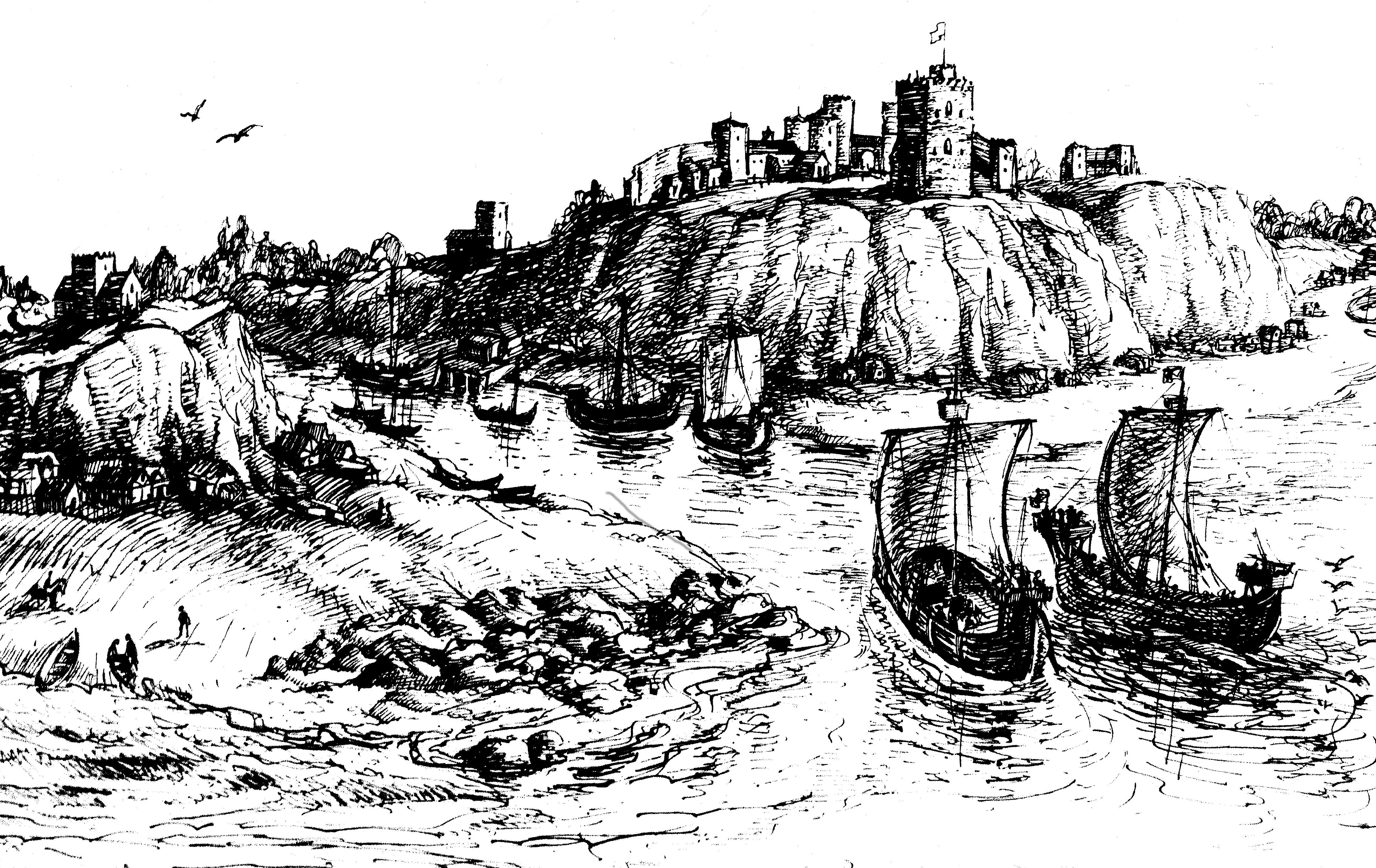

There was almost certainly some form of port at Hastings right through the first millennium AD, using at least the natural shelter of the Priory Valley for as long as possible, depending on the movement of shingle along the coast.

But the narrow Priory Valley could easily be blocked by shingle, and from at least the ninth century there was also an ‘official’ port at Bulverhythe, to the west. This name is derived from the late Saxon words Burhwara hyd, meaning the ‘hythe or harbour of the burgesses’, being the men living in the Cinque Port and Borough of Hastings, to which the area belonged. The haven at Bulverhythe was much larger than the Priory Valley, with many streams running into it that could combat the shingle build-ups. There was also probably a significant settlement at Bulverhythe, on today’s small hill around the Bull Inn on Bexhill Road. That hill would then have been much larger to seaward. Its harbour would have been where the flat land to the north-east is now, with wharfage on the sheltered northern edge of the hill. The large haven of Bulverhythe could have been one of the main landing places that William the Conqueror was aiming at with his large number of invading vessels in 1066, although there is no archaeological evidence of this.

The town of Hastings in the 10th century, and up to the Norman invasion in 1066, was probably centred on a piece of ground that has nearly all been lost. This was the headland at White Rock which then extended much further to seaward than it does today, sloping down to sea level. The church of St Michael probably stood just beyond the seaward edge of today's St Michaels Place on White Rock, and this must have been the most important church in Saxon times, as the town's 12th century seal depicts St Michael slaying a dragon.

There were three other now-lost churches along the mile of coast west of White Rock, showing there was significant settlement of some kind there. St Margaret's stood behind 50 Eversfield Place on the edge of the cliff. St Leonard's Church was to seaward of the western half of Norman Road (the Wesleyan Chapel was built on some of its graveyard). There was a St Peter's Church probably in this western area, but its site is unknown. These churches were probably established in the 12th century, and are all on the earliest list of the town's ancient churches, dated at 1291. The others on the list are St Michael's, the original All Saints and St Clement (both to seaward of their present locations), and St Andrew, which stood a few yards downhill of Castle Hill Road opposite Castledown Terrace.

The Saxon town on White Rock overlooked the port in the Priory Valley, while on the other side of the valley was the West Hill, with possibly a church and some fortifications (the fortress of the burh?) where the castle is now. The West Hill also went further out to sea, while on its east side was the inlet of the Bourne Valley, which may have formed a small port and where some people probably also lived. The East Hill was possibly also used by the Saxons, as what seemed to be a 9th century burial was found on top of the hill when the East Hill Lift was being built.

The late 10th and 11th centuries saw a remarkable economic growth in England, with many new towns emerging by the time of the Norman Conquest. William probably chose Hastings as the first base for his 1066 invasion because it was by then a town of some size with two harbours, being an important trading place, fishing port and cross-Channel communications route. In addition, much of Hastings lay within the extensive manor of Rameslie, which included Rye and Old Winchelsea, that had be given to the Abbey of Fécamp in Normandy by King Cnut in 1017. After the 1066 conquest Hastings was seized by the King and Fécamp was compensated with the Sussex manor of Bury. The castle was given to Robert, Count of Eu, but his land within Hastings was limited to the castle, a park to the north-east, a mill and meadows in the Priory Valley.

Hastings harbour in the Priory Valley, c1100. The town was based on White Rock, on the left. On the right is Hastings Castle.

It was from the late 11th century onwards that the town of Hastings moved, or began to move, into the Bourne Valley, becoming the 'New Hastings', as a contemporary document called it. Somewhat confusingly, 'New Hastings' is now called the 'Old Town', the unofficial name given to it in the 19th century when Hastings overspilled westwards back into the Priory Valley - to form the 'new town' of Hastings, next to the oldest town of Hastings, on White Rock!

During the late 11th and 12th centuries Hastings was both a successful town and an important port. It was then the most dominant of the five Cinque Ports on the Kent and Sussex coast, which supplied naval vessels to the Crown when needed, in return for concessions called 'liberties'. A key liberty for the Hastings fishing fleet for several centuries was the right was to land and sell fish (mainly herring) at Yarmouth. The other four Cinque Ports were Sandwich, Dover, Hythe and Romney.

Hastings was at its medieval peak of importance in the late 11th century and first half of the 12th century, when it headed the list of Cinque Ports. But by around 1200 the harbour facilities at Hastings had decayed, and Winchelsea and Rye had both become wealthy ports, overshadowing Hastings.

From this time onwards Hastings would suffer from both constant coastal erosion, eating into the cliffs on which much of the town stood, and from the long-shore movement of shingle that steadily blocked up the Priory Valley harbour. During the 11th century a shingle spit started developing across the mouth of the Priory Valley, initially providing a safe harbour. But coastal erosion in the 13th and 14th centuries cut back the sandstone cliffs in the Hastings area, especially the White Rock headland, and this allowed large quantities of shingle to be deposited across the mouth of the Priory Valley, ultimately silting it up and forming the Priory marshes, which were finally drained in the early 19th century.

Severe storms in the 13th century, culminating in the 1287 hurricane that destroyed Winchelsea, washed away most of the 'new town' of Hastings in the Bourne Valley, forcing the rebuilding of much of it further inland. The part of today's Old Town south of Courthouse Street may be what was then the inland section of the 11th/12th century 'new town' which survived these 13th century storms. But in contrast, the area of the Old Town north of Courthouse Street must have been laid out in one phase after the storms, as the building plots are of roughly equal size, and there are long raised pavements in both High Street and All Saints Street which would have to be created before the houses were built on them.

French attacks on the town in 1339 and 1377 hastened the decline of the town, and by about 1400 Hastings was little more than a minor port, based mainly on its fishing industry, with a derelict castle. However, in 1580 a group of local landowners and traders obtained a large grant from Queen Elizabeth to create a 'haven' (a form of marina) in the Priory Valley which could provide berths for commercial vessels. An embankment was built across most of the valley entrance, where Cambridge Road is today, but the scheme was never finished. This embankment shaped the future history of the valley, creating the setting of today's town centre. But in the short term Hastings was to remain largely insignificant, until it started playing a major role in the smuggling industry in the early 18th century, and then also started becoming a popular seaside resort in the 1780s.

Much more detail on the history of Hastings - and its 19th century neighbour St Leonards - are in the following chapters of the Chronicle, starting in 771.