The Cyril and Lilian Bishop was the RNLI lifeboat stationed at Hastings from 1931 till 1950, during which time she is known to have been launched 99 times and to have saved at least 34 lives.1 In addition, she may have saved possibly hundreds more lives while taking part in the evacuation of British and allied troops from the beaches of Dunkirk in 1940.

Key FactsThe Hastings lifeboat for 19 years, from 29 April 1931 |

Click here to open the big 'Cyril and Lilian Bishop' gallery in a new page

Before the Cyril and Lilian Bishop came to Hastings in the spring of 1931 there had been five lifeboats at Hastings. The first was the Aerial, from 1835-52, a little-used open row-boat paid for by local donations. The first RNLI lifeboat was the Victoria, installed at Hastings following the loss in a gale of four sailors when a 67-ton trading vessel capsized in front of a large crowd of people at Rock-a-Nore in October 1857.

The Victoria, a ten-oared row-boat, arrived in Hastings in April 1858, remaining on duty until 1863, when she was replaced by a larger 12-oared row-boat, also called the Victoria. This vessel was renamed the Ellen Goodman in 1867, and remained at Hastings until 1880. A contemporary model of the Victoria/Ellen Goodman, or of that design of lifeboat, is on display in Hastings Museum and Art Gallery.

In 1880 she was replaced by the Charles Arkcoll, and was accompanied by a new lifeboat station, built in 1882 on the seafront opposite the Cutter pub. This impressive station succeeded the first one, built in 1858 at Rock-a-Nore. In the Fishermen’s Museum there are two contemporary models of the Charles Arkcoll, one including part of the new lifeboat house. She was followed by the Charles Arkcoll II, from 1901-31.

That year she was replaced by the Charles Arkcoll, and was accompanied by a new lifeboat station, built in 1882 on the seafront opposite the Cutter pub. This impressive station succeeded the first one, built in 1858 at Rock-a-Nore. The Charles Arkcoll was followed by the Charles Arkcoll II, from 1901-31.

The two Charles Arkcolls were sailing and rowing vessels, but the Charles Arkcoll II was replaced in 1931 by the motor-driven Cyril and Lilian Bishop as part of a nationwide programme by the RNLI to modernise all its fleet. The Hastings station was given priority in this change-over following the tragic loss of the Rye Harbour lifeboat and all 17 of her crew in a severe gale in November 1928. This disaster led to that station's closure, and the resulting widening of the Hastings station's area of responsibility to Dungeness. The RNLI quickly reacted to the Rye Harbour loss by announcing in late March 1929 that Hastings would soon be receiving its first motor lifeboat.

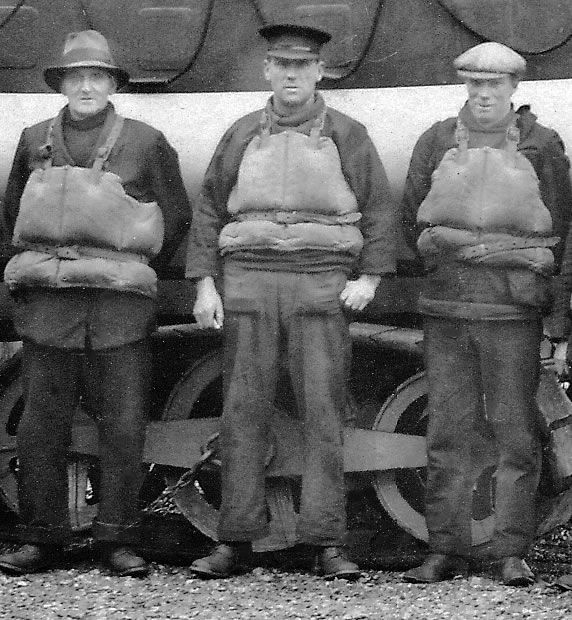

Also in 1929 the 67-year-old lifeboat coxswain Jack Plummer retired after 33 years service, 26 of them at Hastings. Twenty six lives had been saved under his personal command. He was succeeded in August that year by the-then second coxswain, Will ‘Ickle' Curtis, skipper of the biggest Hastings fishing boat, the EVG RX 152. Curtis had been in the Charles Arkcoll II almost as long as Plummer, his first service being to aid the large ship Lugano in 1906. Will Curtis was to be the first coxswain of the Cyril and Lilian Bishop, from her arrival in 1931. He was coxswain until 1939, and then again for part of the Second World War, and he was to be the Cyril and Lilian Bishop’s longest serving coxswain, for 10½ of the boat’s 19 years at Hastings.

Building the Cyril and Lilian Bishop

The keel of the new Hastings motor lifeboat was laid on 27 June 1930 at the shipyard of J Samuel White and Company, beside the River Medina in Cowes on the Isle of Wight. This long-established company built a wide range of naval and mercantile vessels, with shipyard berths capable of accommodating ships up to 350 feet long. At West Cowes there was a department specially set apart for the building of RNLI lifeboats, capable of constructing 12 boats at the same time.

In November 1929 The Engineer magazine reported that Messrs White had completed 42 lifeboats in the past nine years, and were then building ten RNLI motor lifeboats of three different sizes. The main timbers or ribs of these boats were of Canadian rock elm, while the boats’ skin took the form of double diagonal planking of Honduras mahogany secured with clenched copper nails and screws, and fitted with a layer of calico between. There was a self-emptying cockpit (also called locker, air-box and end-box) at each end of the vessel, plus over 100 buoyancy chambers - small air cases, made of wood, fitted in all side spaces.2

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop was one of the recently-developed light self-righting type of lifeboats. At 35ft 6ins long and 8ft 9ins wide she was almost the same size as the Charles Arkcoll II. But the installation of the 35hp, seven knot petrol engine meant that the new boat had to be more heavily built, which, with the weight of the engine, made her twice as heavy as the old 3½ ton craft.3 This was to cause some difficulties in launching at Hastings, particularly at low tide across the sand, and necessitated having more helpers. The new lifeboat looked very much like her predecessor, except for a small rounded cabin. She also had sails (foremast lug and jib) to assist the engine, or to replace it in a breakdown. She had a top speed of 7¼ knots and could self-right in 12 seconds.

The £4,500 cost of the Cyril and Lilian Bishop was met by a wealthy English woman, Lilian Philpott, who committed suicide just eight days before the new lifeboat was delivered to Hastings. Lilian, aged 49, took her own life by gas poisoning in her luxurious apartment in Lower Sloane Street, Chelsea, on 21 April 1931.

She had been born on 12 July 1881 as Lilian Baldock, the daughter of Colonel Edward Baldock (1853-1913) who lived at 8 Grosvenor Gardens, Belgravia. He had inherited great wealth from the land and property purchases of his father of the same name, who had been MP for Shrewsbury.

Lilian’s mother was Agnes Bibby, part of the rich family that ran the highly successful Liverpool-based shipping business called the Bibby Line. This was set up in 1807 and remains in operation today as a wide-ranging business operation, and which is one of the longest established family-owned companies in the UK. Agnes married Edward Baldock in 1880, and in 1885 her father James Bibby gave her a large house and surrounding land in Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire. The Bibby family home at that time was the magnificent Hardwicke Grange in Shropshire, and Agnes was a country girl at heart.

Her daughter Lilian therefore grew up in a high class world, with luxury homes in London and the countryside. She became an attractive young socialite, most eligible to continue living in the higher layers of British society, and she was part of two wealthy families, the Baldocks and Bibbys.

Lilian was also the only child on her father’s side of the Baldocks and of her mother’s branch of the Bibbys, and she would therefore inherit large estates on their deaths. Her parents were happy with this until in 1903 Lilian fell in love with a young motor mechanic in Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire. On her 1903 birthday Lilian’s father Edward had given her a car as a present, and had recruited local garage owner Cyril Bishop to help her learn to drive in the picturesque lanes around Melton Mowbray. Cyril, born in 1883 in Sidcup, Kent, was said to be handsome and debonair, and it soon became clear to Lilian’s parents that a downgrading marriage was a distinct threat. First they tried to make life too uncomfortable for Cyril, but this was unsuccessful, so Cyril was then offered a large sum of money to go away, which he refused.

Despite this family opposition, the marriage of ‘rags and riches’ took place in June 1905 in St Peter’s Church, Belgravia. The couple subsequently lived in a nearby delightful apartment block: Burton Court, Lower Sloane Street, where they enjoyed a comfortable life over the next few years. But Lilian sadly had no child, and there was another great sorrow when, on 4 February 1911, Cyril died suddenly at home, aged just 28, possibly of some form of heart disease.

However, Lilian soon met another young man whom she liked, and in the summer of 1912 she married 28-year old Cecil Philpott, a native of Kent, whose family were brewers.

Lilian’s father Edward died in 1913 after a long illness, with his wife Agnes surviving another nine years until dying in 1922. Both were buried at Buxted Parish Church, Sussex, as the Baldocks had owned property in that area for many years. It was on the death of her mother, and her own childlessness, that Lilian inherited fortunes from both parents and became very rich, able to live the most comfortable life.

But on 20 April 1928, her second husband Cecil died aged 47 at their home in Lower Sloane Street. His death seems to have had a profound effect on Lilian, for she committed suicide there three years later in 1931, almost on the 3rd anniversary of Cecil’s demise. Her reasons are unknown, but she may have felt despair at her loss of two husbands, her lack of immediate family and her social isolation after having married the ‘lower-class’ man Cyril.

On her death, Lilian’s estate had a gross value of £245,000. There were 26 valuable properties in Oxford Street (including a Midland Bank), Tottenham Court Road, Mayfair, the City and Highgate, with a total annual income of £6,300. They were auctioned on 22 July. In her will she bequeathed over £90,000 to charities, many being health-related.

Between Cecil’s death in 1928 and her own suicide in 1931, Lilian also gave enough money to the RNLI to build two new lifeboats, which were to be named after her and her late husbands. Lilian may have wanted her donation to be used for lifeboats in Sussex, as Buxted, near Uckfield, had been the home of the Baldocks family.

The first new lifeboat was the Cecil and Lilian Philpott, in memory of her second husband, based at Newhaven from 1930 to 1959. She was built in 1929-30 by Messrs White & Co, at Cowes.4 She was a 45ft 6ins Watson class boat, with two 40hp petrol engines. Her official christening was carried out by the Duke of Kent on 7 July 1931. She took part in the Dunkirk rescue in 1940, and remained at Newhaven until being put in the RNLI reserve fleet in 1959. She was sold in 1969 to a doctor, who converted her into a family cruiser, and renamed her Stenoa. She is still in good condition, is based at Walton-on-the-Naze, and has joined in the Dunkirk commemoration events.

Lilian’s second new lifeboat was the Cyril and Lilian Bishop, named after her second husband, which arrived in Hastings on Wednesday 29 April 1931.

On Station

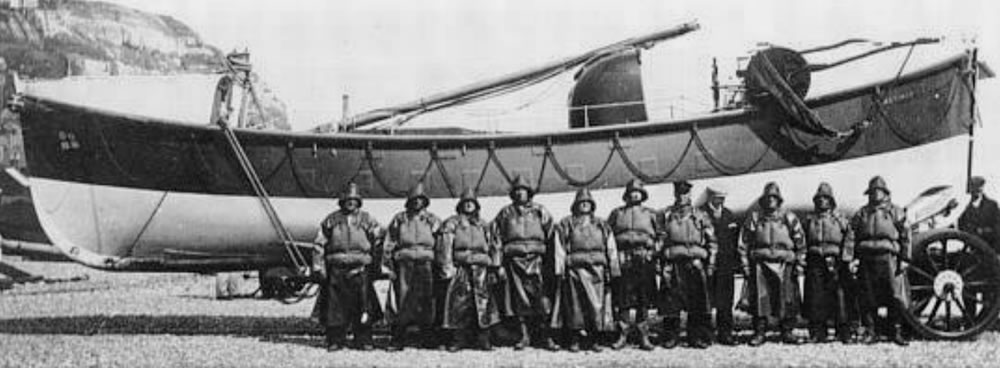

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop was brought from her builders at Cowes by Coxswain Will Curtis, bowman Frank Martin, Fred Doughty and the first-ever Hastings lifeboat mechanic, Bill Hilder. As the boat approached the Old Town on 29 April two maroons were fired and a large crowd gathered to welcome her as she ran onto the beach at 12.30pm.

Coxswain Curtis told the Hastings Observer ‘The Cyril and Lilian Bishop is a fine craft, and a smart one - every inch a boat. She handled very well and is quick on the helm. The motor ran beautifully.’5 A trial launch was made on 30 April, including a trip to Fairlight for signalling tests with the Coastguard station on Fairlight Head.

On 26 May the retired lifeboat Charles Arkcoll II was auctioned outside the lifeboat house. Bidding was slow, but after ten minutes the proud old vessel was knocked down for £50 to two Hastings taxi-drivers. They planned to convert the boat into a passenger-carrying pleasure craft, operating out of Rye Harbour. They installed a 14hp engine from a Vauxhall car, but their maiden voyage in June, 1932, came to a sudden stop when they were stranded for several hours at the river mouth.

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop was an undoubted improvement on her predecessor. Her engine enabled her to launch in more severe weather, as it provided more power to drive the boat out through the surf. With an engine, the boat was also much less likely to be pushed to leeward along the shore by the wind while launching, thus making launching safer and easier, and enabling more use to be made of the harbour for launches. Once afloat, the motor lifeboat was much more versatile, as she could travel longer distances faster, could head straight into the wind if necessary, and involved much less hard work for the crew. This greatly improved efficiency was to help overcome many of the old problems that had bedevilled the earlier lifeboats.

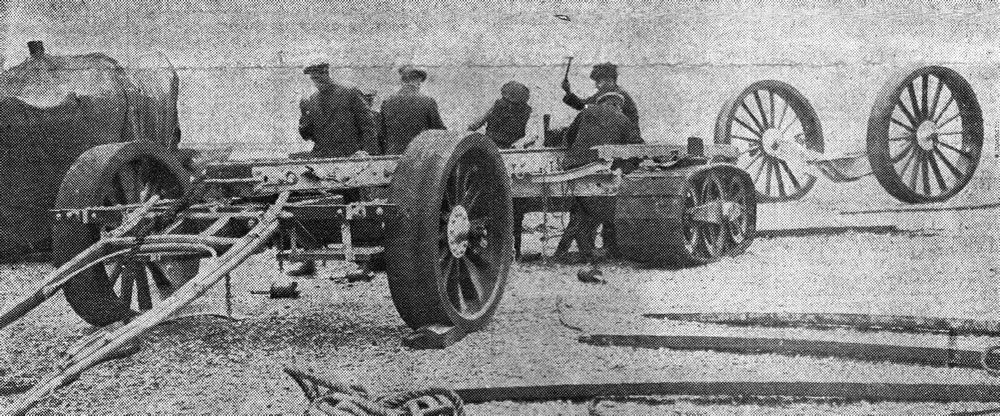

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop did bring some problems, however. Her increased weight meant that the rear wheels on her launching carriage had to be replaced straightaway by tracks to stop the carriage sinking into the beach. Also, more help was needed for low water launches, with 30-40 people, sometimes having to go right into the sea, and being entitled to a small payment. This, plus the generally greater expenses of a motor vessel, helped to increase the running costs of the new boat to roughly £400 a year. The smaller crew - usually nine - made a financial saving, but overall the new lifeboat gave the local RNLI committee much more fundraising to carry out.

A glimpse of the future was seen in late July 1931 when an experimental caterpillar tractor replaced human power in two low-water trial launches. These were the first tractor-assisted launches on the south coast, but Hastings was to continue with hand-launching until 1963.

Another experiment of the early 1930s was with wireless communication. Until this time RNLI officers on shore kept in contact with the lifeboat at sea by semaphore flags and flares during the day, or rockets at night. This was a far from satisfactory system, as it relied on the boat being visible, which it often was not in bad weather, and on the crew keeping a constant eye on the shore for messages. In the spring of 1934 local wireless enthusiast CS Bradley offered to carry out experiments on the lifeboat, and the first of these was successfully conducted on 27 April 1934. The tests went on for more than 18 months before a set was installed in the Cyril and Lilian Bishop on 7 August 1936. This was a four-valve, crystal-controlled receiver, permanently tuned in to a 25 watt transmitter at the lifeboat house. The receiver was fitted in a copper box near the stern of the boat to cut down interference from the engine. Messages were received over headphones, but the equipment could not transmit.

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop was christened in front of a large crowd on Friday 21 August 1931 by Viscount Goschen, a ‘native of Hastings’.6Amid loud cheers from hundreds of onlookers, he named the boat after shattering a bottle of wine on her bows as she stood on top of slipway a near the harbour. Coxswain Will Curtis then blew his whistle, the retaining chain was knocked away, and the Cyril and Lilian Bishop then slid rapidly into the breaking waves to start her inaugural cruise in front of thousands of holidaymakers.

Rescues in the 1930s

During her 19 years at Hastings, from 1931 to 1950, the Cyril and Lilian Bishop was launched 99 times and saved a total of 34 lives. Nine of the 34 were rescued in the 1930s, before the start of the Second World War in September 1939.

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop's first life-saving rescue took place on Saturday 8 August 1931, when the three crew of the yacht Falcon were rescued just off White Rock. The man and two women were on holiday and trying to make Newhaven in bad weather, but the struggle was too much for them, and they dropped anchor at 4.30am just to the east of Hastings Pier, suffering from exhaustion. But they were perilously close to the Castle Rocks and the sea was rough, so at about 11.30 they hoisted distress signals. The new Hastings lifeboat was launched in just 11½ minutes and soon came alongside the tossing vessel, watched by thousands of holidaymakers on the seafront. The two women both fell into the sea as they tried to board the lifeboat, but were quickly rescued, and the trio were then landed safely at the harbour. Coxswain Will Curtis said that the rescue was accomplished much more easily in the new motor vessel than it would have been in the old lifeboat. The Falcon broke from her mooring soon after the rescue and drifted ashore at Carlisle Parade, where she broke up in heavy seas.

In the opening months of 1933 Hastings Council built a large boating lake between the lifeboat station and the sea, using unemployed men for the work. This meant that from April 1933 onwards the lifeboat had to be taken 200 yards westward along the promenade and around the west end of the lake to be launched, increasing the launching time.

Will Curtis and other lifeboat crew members saved the two-man crew of a large spritsail barge which was driven ashore at Rock-a-Nore in a gale early on the morning of 18 August 1933 - but without using the lifeboat. The barge Elsie had been anchored in Hastings harbour, sheltering from the weather, but her anchor cable broke. The lifeboat men and coastguards used rocket apparatus from the shore to fire a line onto the stranded vessel and haul the crew ashore. Later that day the Elsie was towed to Rye Harbour by the fishing boat Boy Billie RX 61.

The second life-saving mission by the Cyril and Lilian Bishop was on 13 February 1935, for two Hastings fishermen in the small fishing boat Gipsy Queen RX 10. George Mitchell, aged 18, and John Payne, 20, were sprat-catching 1½ miles off Fairlight that morning, when their engine broke down. George’s father John Mitchell, owner of the boat, sent another of his boats, the Fairlight Belle RX 71, to tow the Gipsy Queen home, but in the rough seas the tow-rope broke just as the boats came to Rock-a-Nore. It was low tide and launching the Cyril and Lilian Bishop proved very difficult. George’s mother collapsed and other women relatives of the crew were weeping as the lifeboat crew and launchers struggled to get the vessel afloat. But eventually they succeeded, and the crew and boat were saved.

Another two fishermen in a small fishing boat were rescued by the Cyril and Lilian Bishop on 18 November 1936. The brothers Bert and Jack Payne, working for fish salesman Jack Adams, were hauling nets aboard the Little Culverden RX 12 in heavy seas about 2½miles south of St Leonards Pier when water entered the boat and stopped the engine. They managed to keep the boat afloat by bailing, and were totally exhausted when rescued by Will Curtis and crew.

Two men and a dog were saved on 29 July 1937 when their 25 ft speedboat Ski Queen broke down off Fairlight Glen They were spotted by Fairlight Coastguard, at anchor dangerously close to the shore. The men were from West St Leonards, where they used to tow aquaplanes, and were taking the craft to Rye Harbour, but the sea got up and swamped the engine. The lifeboat rescued them and towed their boat back to Hastings.

A few weeks after this, in early September 1937, the old horse-turned capstan used for hauling the lifeboat up the beach at Hastings was replaced by one powered by electricity.

Ironically, the Hastings lifeboat's most difficult mission in the 1930s did not directly result in the saving of life. This was during the ‘Derby Day Gale' on 1 June 1938, when ten Hastings fishing boats were caught at sea in a sudden storm. There was a series of severe gales around much of the British coast from 31 May till 2 June, resulting in the launching of 32 RNLI lifeboats.

The Hastings Observer reported that the ‘Cyril and Lilian Bishop went through the severest ordeal of her career on Wednesday night [1/2 June], when for three hours she battled with a full gale and heavy seas in a search in Rye Bay for three missing Hastings fishing boats after she had escorted four others safely to harbour.’7 The ten boats were out on Wednesday evening, some in Rye Bay, others near the Royal Sovereign lightship, when, within a few minutes, what had been a moderate breeze blew up into a strong south-wester that rapidly approached gale force.

The lifeboat’s launching maroon was fired at 9.30pm and was afloat at 9.44. This had been done with great difficulty, as it was low water, and 65 men had to drag the boat into the breaking surf. Three of the ten boats made it ashore as the lifeboat was being launched: George Haste’s Henry Harris RX 2, the Mayflower RX 289 and the Two Bessies RX 81.

The lifeboat then escorted four others to safety: Bill Terrell’s William and Edwin RX 52, Biddy ‘The Tubman’ Stonham’s Unity RX 301, the Young Mayflower and Tom ‘Toller’ Adams’s Boy Bob RX 330.

After this it was believed that the three other boats had made it to Rye, and the Cyril and Lilian Bishop returned to station at 11.45pm. But she was almost immediately relaunched when news was received that one of the boats had broken down off Winchelsea Beach. The lifeboat under second coxswain George Moon then spent three hours searching Rye Bay for the three boats: Cllr Edward Breeds’s Edward and Mary RX 74, the White family’s Flying Fish RX 242 and the EVG RX 152 which was skippered by lifeboat coxswain Will Curtis. The Observer said: ‘While the lifeboat battled with the heaviest seas she had ever experienced in a vain quest for the missing boats, wives and relatives of the men aboard them waited on shore with deepening anxiety.’

The search was called off at 2.40am when it was learned that the EVG had successfully entered Rye Harbour, and that the Edward and Mary and the Flying Fish had run ashore at Camber, but were not in danger. Many of the fishermen said the weather was awful and the worst they had experienced.

On 4 June George Moon spoke in the radio programme In Town Tonight of his experiences being in command for those five hours of the worst weather the lifeboat had experienced until then.

The Start of the Second World War

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop earned a distinguished life-saving record during the Second World War, and also suffered the only known complete capsize of a Hastings lifeboat. The boat saved an unknown, but possibly substantial, number of soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk, plus another 21 lives in 48 other recorded launches. ‘Sometimes,’ later recalled the local RNLI secretary Commander William Highfield, ‘they only found something to show they had reached the right spot - a patch of oil or a piece of parachute fabric.’ The lifeboat was also ordered to stand by 26 times by the Naval authorities.8

Lifeboat coxswain Will ‘Ickle’ Curtis, aged 61, retired at the end of December 1938 after 38 years service. The RNLI’s official retiring age was 60, but Curtis was allowed an extra year. He had been coxswain since 1929, and second coxswain for seven years before that. For most of this time he had been living at the bottom of All Saints Street, number 73. Curtis had been skipper of the fishing boat EVG RX 152 for many years, and in January 1939 he bought her from the owner, Edward ‘Woolly’ Tassell. She sank after hitting a mine in Rye Bay on 17 March 1943.

Curtis was succeeded in January 1939 by George Moon, but after the Dunkirk evacuation in 1940 Moon joined the forces, and Curtis then returned until early 1943, when he became ill and could not carry on. He died on 25 February 1950.

Former second coxswain John Edward ‘Ned' Muggridge was discharged from the Navy on medical grounds in late 1942, and he replaced Curtis as coxswain on 1 February 1943, but was killed at sea on 10 April 1943 when his fishing boat Boy Billie RX 61 was blown up by a mine. Then Edward ‘Ned Wintry' Adams, skipper of the Industry RX 94, took over, staying coxswain until 1950.

The war was only six days old when the Cyril and Lilian Bishop was called out for the first time in the five years of conflict. At 9.30pm on 9 September an RAF Avro Anson aircraft, K8707, was seen crashing into the sea, about a mile east of the Fairlight Coastguard lookout. The Pett Level life-saving motor boat found the aircraft still afloat, with the crew of four sitting on top of it, and landed them at Pett Level. The Cyril and Lilian Bishop towed the plane back to Hastings, where it was hauled up the beach, attracting large crowds on the following day.

On 13 November 1939 the small Hastings fishing boat Sea Queen RX 105 broke down close to a ledge of rocks near Fairlight Cove. The two fishermen on board fired flares, which were seen by the Coastguards, and the Cyril and Lilian Bishop towed them back to the harbour.

Three fishermen were rescued on 9 February 1940 from their boat Venus of Rye, which had run aground less than 400 yards off Winchelsea Beach. The three were brought back to Hastings, with the skipper, Alf Fowle, being taken to hospital with a minor leg injury.

On 20 March 1940 the 5,439 ton steamer SS Barnhill was the first British merchant ship to be sunk by an enemy air attack in the English Channel. Carrying a cargo of general goods, she was bombed and caught fire, south of Beachy Head. Five members of the crew were killed, and the Eastbourne lifeboat Jane Holland rescued the 29 survivors. The half-wrecked ship gradually drifted towards the land, finally running aground near Langney Point, where her remains can be seen at very low tides today. The Hastings and Newhaven lifeboats were launched to help Jane Holland.

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop returned to the SS Barnhill area early on 7 December 1940 to rescue two soldiers who had been clinging to the nearby wreckage of a small boat. They had been in the icy water for 16 hours after setting out the previous afternoon to do some fishing.

1940: Dunkirk

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop played a significant lifesaving role in Operation Dynamo, the codename given to the evacuation of 338,226 Allied troops from Dunkirk, France, between 27 May and 4 June 1940.

The operation was launched when large numbers of British, Belgian and French soldiers were cut off on 23 miles of the French coast east of Calais and surrounded by the German army during the Battle of France. The only French or Belgian port in British hands was Dunkirk, and 239,446 of the troops were able to embark from that harbour and its breakwater onto 39 British destroyers and other large ships.

But 98,780 men had to be ferried out from the 16 miles of beaches between Dunkirk and Nieuport to ships waiting in deep water. Despite much attacking by German aircraft, these stranded troops often had to stand in long queues going out into the sea. The ferrying boats that rescued them and transferred them to larger vessels were shallow draught craft that became known as the ‘Little Ships’ of Dunkirk: yachts, sailing barges, fishing boats, pleasure craft, paddle steamers and lifeboats, all called into service in the emergency. Nineteen RNLI lifeboats, including the Cyril and Lilian Bishop and the Cecil and Lilian Philpott of Newhaven, were part of the armada of ‘Little Ships’.

At 1.15pm on Thursday 30 May the Ministry of Shipping telephoned the RNLI headquarters in London and asked it to send as many lifeboats as possible to Dover at once. The RNLI immediately requested that its 19 lifeboats stationed between Gorleston in Norfolk and Shoreham in Sussex should go to Dover. The crews of two of them - the Prudential of Ramsgate, and the Lord Southborough of Margate - had already volunteered, and they set sail for Dunkirk that Thursday afternoon.

The first three of the other lifeboats to arrive at Dover were from Hythe, Walmer and Dungeness. Historian Mr AD Divine DSM, who took part in the evacuation, wrote in 1945: ‘When the coxswains and crews ... arrived at Dover and were informed that their task was to take men off the beaches, they demurred on the ground that, on a falling tide, they would inevitably be stranded and lost [because the shape and weight of the boats meant they could not ‘take the ground’]. There was no time for argument, and the Admiralty immediately took over completely the three boats which had raised the objections, manning them with naval crews; and, considering that what applied to some might apply to all, they - to the considerable indignation of the boats which came after from [the other stations, including Hastings] - announced that naval crews would take over, and that they were only prepared to utilize the services of mechanics.

‘This decision was a difficult one, but in these days hours counted. There was no time for discussion, little for explanation. It was acknowledged that there was substance in the objections, but the situation demanded every possible degree of speed. The decision stood.’9 On the evening of 31 May RNLI lifeboat inspector John Upton went to Dover to try and resolve the manning problem, but he was too late, as the disappointed crews were already on their way home.

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop went to Dover under the command of Coxswain George Moon. His great-nephew Kevin Boorman said: “George was extremely disappointed not to be allowed to take the Cyril and Lilian Bishop across to Dunkirk. I was told that the Hythe crew had refused to go not because they were scared, but because they were worried about the impact of taking the boat would have on their home patch - they had been very busy indeed in the days leading up to Dunkirk.”10

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop, which had the official number 740, was put under the command of acting petty officer Mr WH Adkin. The Hastings Observer reported on Saturday 8 June 1940: ‘During the weekend [1st and 2nd], it is understood, the lifeboat was taken across to Dunkirk, and helped to bring off men of the forces to waiting war vessels. The boat, bearing many honourable scars and leaking slightly, was brought back to Hastings by the crew on Wednesday [5th].’ There was a hole in the port side of her bow, and it was clear from the Cyril and Lilian Bishop’s general condition that she had been well used.

Bill Terrell, a Hastings fisherman and a member of the scratch crew that took the Cyril and Lilian Bishop to Dover, later recalled his memories of what had happened. ‘We'd been off fishing during the night [of 29/30 May], so when we came ashore early morning we went home to bed. When we got up later in the morning and went down the beach all the other [fishing] boats were off. I said to my brother "Someone must have had a good catch!" After a while we found that they'd all gone to Dover.

‘After dinner we went down the beach again and George Moon came running along, saying "I've had orders to take the lifeboat to Dover — will you make up the crew?" Me and my brothers Jim and Ted said yes. The only three regular members of the crew on the trip were George Moon the coxswain, Bill Hilder the mechanic and Will Martin the second mechanic. The others that came were Charlie ‘Bodger' Barton, ‘Jumbo' White and Fred Button. We left Hastings beach near enough 4.00 that afternoon [30th]. All boats had to be in a harbour by sunset, otherwise they'd be fired on, and where it was getting dark when we were off Folkstone we put in there. We slept the night on the floor of the Seamen's Mission.

‘Next morning [31st] we got up about 5.00, went along the cafe, had a bit of breakfast, went back to the lifeboat and proceeded to Dover. When we got there we went to the Admiralty survey boat that was giving orders. They told George Moon we'd have to go across from one buoy to another to avoid the mines. He asked if we could have a machine gun on the foredeck — they said no. He said can we have a rifle — they said no, all you can do is go to the Prince of Wales Pier, load up with petrol and get what food you want.

‘So we went to the pier and got out of the boat. I don't know where the others went, but George Moon went to see about the petrol and Bill Hilder and myself walked along the parade and then came back. Then we saw two sailors in the lifeboat. Bill got wild and shouted "What are you two doing in there?" They said "All we want to do is start this engine." George then said that all lifeboats had been commandeered by the Navy — we had to get railway warrants and come home.’

The evacuation ended on Tuesday 4 June, with all vessels ordered to leave Dunkirk by 2.30 that morning. The Cyril and Lilian Bishop’s regular crew brought her home from Dover on 5 June. Bill Terrell said: ‘The boat had just been painted up. When she came back to Hastings they found sand in her forward locker and in her masthead light, so she might have capsized.’11 There was a hole in the port side of the forward locker, and there were many scratches on the hull below it. Plus there was a thick line of mud along the port side of the boat, indicating she may have become stuck in mud at some point while close to shore at Dunkirk. A bullet was found below deck, showing she must have suffered from at least one aircraft attack.

Just how many soldiers the Cyril and Lilian Bishop saved is not known, as no official record was kept of what all the lifeboats did at Dunkirk. However, it is understood that the Ramsgate lifeboat brought about 2,800 men off the shore and on to waiting ships in two days, the Margate lifeboat some 600 men in one day and Newhaven’s Cecil and Lilian Philpott over 600 troops in nearly three days. As the Cyril and Lilian Bishop played a similar role to these vessels, she could have rescued many hundreds of soldiers.

A Royal Artillery gunner, Roland Thurlow, told his children after the war that he had been at Dunkirk and was one of a large group of soldiers picked up by a lifeboat. He had then been dropped off at Hastings, and was probably on the Cecil and Lilian Philpott which was making its way back to Newhaven. The only RNLI lifeboat lost during the evacuation was the Viscountess Wakefield, of Hythe, which was run onto the sands but was too heavy to get off, and so was abandoned.

All the larger Hastings fishing boats had gone to Dover on 30 May to possibly take part in the Dunkirk evacuation, but there is no record that any of them did so.

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop was quickly repaired after returning on 5 June, and was able to launch on Sunday 9 June in search of a lost rowing boat, found abandoned near Ecclesbourne Glen.

About three weeks after the completion of the Dunkirk evacuation, the Hythe lifeboat coxswain Buller Griggs and his brother Dick, the mechanic, were summoned to attend to an RNLI inquiry at Hythe Town Hall. This looked into the ‘circumstances in which the crew of the Hythe lifeboat ... declined to take their boat across the Channel’. On 26 June the RNLI said both had been dismissed from the service, with Buller being particularly to blame, because he had ‘induced not only his own, but the crews of two other boats [Walmer and Dungeness] to refuse to take their boats from Dover to Dunkirk’. Buller Griggs, who had served 38 years in the RNLI and had been awarded a silver medal for bravery, denied the claims, saying ‘his boat should not be run onto the beach at Dunkirk or it could not be refloated’, reported the Kentish Express on 25 April 1980.

In 1943 Bill Terrell, also a carpenter by trade, served as a petty officer aboard HMS Belfast, and in his spare time he made a highly accurate model of the Cyril and Lilian Bishop, mounted on its carriage and with a horse to draw it. He lived at 38 Tackleway, and while at sea he sent the beautiful model to his four children at home as a Christmas present.12 Mr Terrell was on HMS Belfast on Boxing Day 1943 when it played a prominent part in the destruction of the German battle cruiser Scharnhorst.

More 1940 Rescues

The aerial combats and bombings of the Battle of Britain from July to October 1940, and the Blitz from September 1940 to May 1941, brought a large number of crashed aircraft that the lifeboats of Kent and Sussex had to deal with.

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop rescued at least four enemy airmen shot down in separate incidents. But there was considerable hostility towards these fliers, particularly to those who had been bombing and machine gunning Hastings. After being pulled out of the sea one shivering German pilot was given a pullover by a lifeboatman, followed by a hefty kick. When the pilot was put ashore at the harbour he gave a Nazi salute, prompting the coxswain to shout ‘Hit the bastard with an oar!' A hostile crowd on the beach looked like giving him far worse treatment until the military authorities intervened.

Many fishermen and lifeboatmen were inclined not to attempt to save enemy airmen, particularly as many of them were armed, but coxswains such as Will Curtis insisted on going to rescue them in case they were of use to the intelligence services. The Hastings Observer commented: ‘No one must be surprised if some, at least, of the lifeboatmen, go unwillingly, knowing what other lifeboatmen and seamen generally have suffered because of the execrable notions of total war which possess the distorted minds of the Nazis and lead them to perpetrate their crimes against humanity and the humanities.’13

Four Germans were rescued by the Cyril and Lilian Bishop during the war. The first was a 25-year old airman early on Sunday 25 August 1940 when his bomber, a Heinkel HE-111, was shot down by a Hurricane about a mile off Ecclesbourne Glen. He bailed out of the blazing aircraft, which had been riddled with bullets, and was the only survivor of the crew of five. He was put ashore and handed over to the military authorities.

Just eleven days later, a Nazi pilot was rescued by the lifeboat on Thursday 5 September when his plane was brought down by a Spitfire. The Hastings Observer reported: ‘The enemy aircraft [a Messerschmitt 109 fighter] was hotly pursued right across the town. The British pilot raked his opponent with a final burst of machine-gun fire almost over the centre of the town, sending him headlong into the sea. The plane vanished instantly beneath the waves. The Spitfire pilot circled round the spot, and then gave the ‘Victory roll’ to the delight of onlookers on the seafront.’14 The pilot, a ‘dark-haired young fellow’, was brought ashore by the lifeboat and an armed escort took him to hospital.

Hastings suffered four days of bombing from 22 September 1940, causing widespread damage throughout the town. On 27 September a British squadron of fighters chased a group of German aircraft away from Hastings, shooting down three of them into the sea. The Cyril and Lilian Bishop rescued a badly-injured aviator, Gefr J Feichtmayer, who was seen clinging to a wooden box after his aircraft, a Junkers Ju-88 bomber, went down off the St Leonards Bathing Pool. At the same time it was reported that another German plane had gone down in flames six miles further south, but the lifeboat could find no trace of it.

The fourth German airman to be rescued by the lifeboat in two months was the pilot of a Messerschmitt 109 which had been engaged in an aerial battle high over Hastings on 22 October. The plane fell into the sea off Fairlight, where the 19-year old man was found in a rubber dinghy. He was handed over to the police and military authorities.

Also in 1940, the Cyril and Lilian Bishop was launched on 13 July at 4.30pm to investigate a water-logged boat seen by the Coastguards about a mile off Hastings. It was without sails and oars, but had clothing and a typewriter aboard. It was brought ashore, while meanwhile another boat had been reported drifting, bottom up, off St Leonards. This was also brought in, and the lifeboat went off a third time to see if there were anything else, finding a third empty craft.

These empty vessels turned out to be lifeboats of two sunken merchant ships. The first and third were from the 3,520 ton steamer SS Kolga, of Tallinin, bombed off Dorset on 4 July. The third lifeboat was from the coaster SS Mallard, of London, which was torpedoed off Bognor Regis on 11 July.

The dramatic year of 1940 ended for the Cyril and Lilian Bishop on 7 December when the two off-duty British soldiers were rescued near Langley Point, Eastbourne; see above.

1941-43

No lives were saved during 1941 and 1942, although the Cyril and Lilian Bishop was launched four times. On 4 January 1941 she was launched after a red flare was seen out to sea. On that day there were ten inches of snow and it was bitterly cold as the men and women of the launch team struggled into the darkness to pull the boat down the beach. But despite a thorough search, no vessel in distress was found.

RNLI records say that two Hastings fishing boats, Boy Ben RX 119 and Two Pals RX 93, had to be ‘escorted’ to Hastings, on 13 July 1941, but no reason is given. Allied forces made an unsuccessful attempt to capture the French port of Dieppe on 19 August 1942, suffering many casualties. The Cyril and Lilian Bishop was launched on that day while the raid was taking place, returning to shore with an aeroplane dinghy and other gear. The fourth launch in those two years was on 2 September 1942, when aeroplane gear was salvaged.

Then in March 1943 the Cyril and Lilian Bishop performed probably the most difficult rescue in her career, receiving several awards from the RNLI as a result.

The Royal Navy minesweeper HMS Caulonia was stranded aground off Jury’s Gap, east of Rye Harbour on the Kent/Sussex border, early on Wednesday 31 March, in the strong winds and rough seas of a south-westerly gale. The vessel was a requisitioned 296 ton trawler, built 1912. Some of the crew reached shore on a raft but seven were stranded aboard the half-submerged craft. The Cyril and Lilian Bishop took two hours to launch in the rough seas, but finally she cleared Hastings harbour and ran before the gale to the Caulonia. In command was Ned Muggridge, making his first trip as coxswain.

At 5.30am they reached the casualty, lying broadside on to the pounding seas, with her fore-part under water. The remaining seven crew were huddled around the funnel.

Charlie Haste, one of the lifeboat crew, takes up the story: ‘We were off Rye before we saw the barrage balloon that was flying on the Caulonia. There was only the funnel, mast and ironwork of the bridge showing above water - all the woodwork had washed away. We went in between her and the shore. Then we saw the chaps on the top of the bridge. There was a hell of a sea running. We tried to motor straight towards the trawler, but when the lifeboat went down on a sea she was smashing on the deck ... when she was up on a sea she was smashing into the funnel or ironwork where the men were hanging on. One sea hit us on the starboard bow and we recovered about 50 yards away from the trawler, full up with water. We had a count up to see if we were all there.

‘After a lot of attempts to get to the chaps, Ned decided to try and get a line to her somehow. We went in a few times before Ned Adams and Fred White, who were up on the airbox (goodness knows how they stayed up there), threw a line which was caught by one of the chaps, who made it fast to the steam pipe that ran up to the top of the funnel. After that we did manage to keep some distance off her. We worked up towards her with the engine and a couple of us on the line, to where Ned Adams threw a second rope, which was caught by one of the men. We told him to make the rope fast round his chest and jump off when there was a bit of a smooth. Well, when the time was right we told him to jump and Dick Harffey and I pulled him through the sea down the port side and got him aboard.

‘We got two more off after a time, then the next one was a bit unlucky. He jumped at the wrong time, because a big sea came as he was being pulled round the bow. He ended up under the lifeboat's bottom, and we couldn't pull him out. Dick and the others were pulling on the line on the port side, and I had his leg hooked with the boat hook on the starboard side. After a time I unhooked him, and they pulled him out and aboard. Then one of the three left didn't have a lifejacket on, so he tied himself to his mate and they both jumped together. We got them alongside but couldn't get them aboard for a long time. The last one, a petty officer, jumped on the lifeboat when her bow was nearly up to the top of the funnel on a sea. We got back to Hastings after a good washing down, and the chaps we saved were glad to get on dry land.’15

The Caulonia rescue brought RNLI bronze medals for gallantry to Coxswain Ned Muggridge and mechanic Bill Hilder, thanks-on-vellum to second coxswain Ned Adams, bowman Fred White and lifeboat secretary Commander Highfield, and £60 17s 6d. (£60.87½p) to be divided amongst the crew and launchers.

Tragically, neither Muggridge nor Hilder lived to receive their medals. Muggridge and another lifeboatman, Dave Coussens, were killed with Charles Page when their fishing boat the Boy Billie RX 61 was blown up by a mine on 10 April 1943, just 11 days after the Caulonia rescue. It proved to be Muggridge's first and only trip as coxswain. Ned Adams succeeded him as coxswain.

Bill Hilder, widely known for the very high quality model boats that he made, was killed on 23 May 1943 when an air-raid bomb destroyed the Swan Hotel in High Street.

On 6 September 1943 Cyril and Lilian Bishop was called out when a large American B-17 Flying Fortress bomber went down into the sea about a quarter of a mile off Bexhill. However, five of the plane’s crew made it ashore in a dinghy and the other five were rescued by local boats, as were the crews of two other Fortresses that had gone down at about the same time in Pevensey Bay.

A convoy of 19 merchant ships was en route from Goole to Poole on 2 November 1943 when it was attacked by a group of German submarines off the East Sussex. The coastal steamer SS Foam Queen, 811 tons, built 1922, was torpedoed by the S-100. Eight men were killed and stern was blown off, but the main part of her remained afloat and was towed to Dover and beached. The Cyril and Lilian Bishop gave help on 3 November.

1944-45: The Capsize

After the dramatic Caulonia rescue, the Cyril and Lilian Bishop's last two life-saving rescues in the Second World War were in 1944. On 10 March the Rye fishing boat RX 133 and her two crew were brought to safety. Then on 19 June a Spitfire went down into the sea off St Leonards, and the lifeboat found the Norwegian pilot in a dinghy. Another aircraft went into the sea on 29 July, but the lifeboat could only salvage some gear.

One of the most traumatic events in the Cyril and Lilian Bishop's history also took place in 1944, but no lives were saved - except, perhaps, some of its crew. On 17 November 1944, while the lifeboat was searching (unsuccessfully, as it turned out) for a military landing craft seen in trouble off Pett Level, the Cyril and Lilian Bishop turned right over, the only time this is known to have happened to a Hastings lifeboat (the Cyril and Lilian Bishop may also have capsized at Dunkirk, but there is no definite evidence of this). Three of her crew, including coxswain Ned Adams, were washed overboard, but were recovered by other members of the crew.

The 1944 capsize took place during a south-south-westerly gale. The lifeboat was launched with difficulty at the harbour at 10.00am, and then ran down to the east. But before the Cyril and Lilian Bishop reached the search area, the landing craft had been forced ashore at Galloways on the Dungeness peninsular, south of Lydd, with the 29 crew managing to get safely onto the beach. Not knowing this, however, the lifeboat crew continued their search, with almost disastrous consequences.

Charlie Haste recalled what happened: ‘Where the wind was blowing right on the shore we were taking all the seas on our broadside. The seas were just running over us as though we weren't there, and she was full on deck all the time. Well, we got down off Winchelsea and over she went. As she started going Dick Harffey and I were on the starboard bow. I don't know what happened to Dick, but I went over down the port side. I found myself, with a rope jammed across my chest, down the back of my lifejacket.

‘I tried to free myself, but then it came into my mind that the boat ought to right itself in so many minutes. It seemed hours to me - I began to black out. I believed I had half Rye Bay inside of me. The next thing I remembered she gave such a shake. When I woke up I was washing to and fro across the deck - she was upright again. The first thing I saw was two hands over the top rail; it was Dick. I grabbed his wrists, but I didn't have any strength left. I had a look aft, but I didn't see anyone at first. I told Dick to put his feet on the side of the boat when I pulled, but his feet went under the bow. I shouted out to Tom Adams, and after he had gone aft to get his brother Ned aboard, he and a couple of hands came forward and we got Dick inboard. Ned went over the wheel, clean overboard. He swam to the boat and was pulled aboard by those aft.

‘Well, then the trouble started. We were in a ripe old mess. Everything that was not lashed down was floating on the water: the spare oilskins, lifejackets, etc - we thought they were some of the crew till we had a count up and found we were all there. The boat was still being swept by seas, as we were lying drifting broadside on. Those aft had started messing about with the engine, grinding the handle, trying this and that, but it wouldn't start. They shouted out to me to get the anchor over to get her head to the sea.

‘This wasn't so easy, what with being half drowned and weak as a rat, and what with all the lashings that were holding down the anchor and the cable being new and shrinking so that we couldn't get them undone. Well, after some time we did get the anchor over, but it had about two fathoms of big chain between the anchor and the cable, which had a big thimble in the end. This thimble jammed in the hawse forward, and nobody could get up there to clear it. We didn't know what to do; we were knocking broadside on towards the shore. We were beazled.

‘Then we had a bit of luck. They happened to get the engine started, but only about a quarter speed - she wouldn't go any faster. We got her head to the wind and the sea, and she just went ahead. Then we found the steering wasn't working right. When the wheel was centred the blade of the rudder was 45 degrees on one side. What happened to it was that when the boat was upside down the blade ran up the square to the top of the sternpost, but when she came upright it came down on the wrong square. Well, we couldn't do anything about that.

‘Now the anchor was swinging about under the water. Every time she went up on a sea it either hit up under her bottom or sometimes came up one side of the bow where we could see it. I got a length of wire, made one end fast on a cleat and waited till it came up one side. After a long time and about a hundred tries I got it fixed to her side. Just after that there came a grand-daddy of a sea. She stood on her stern post, went down backwards under the sea up to the canopy - and then started to go over! I was forward with Dick Harffey and Frank Edmunds, hanging on to anything we could find. We were looking straight down towards aft, or where it ought to be - she was going down sternlong. Nearly half of her was under water, and I thought she was going over again.

‘Then a miracle happened. That shock woke the engine up, and she jumped on full speed. What we didn't know (or I didn't) was that in the fuel system there was a ball to shut the fuel off when she went over. Well, this time when she went over the ball must have shut the fuel off and only partly opened when she came upright again. We still steered her into the wind and sea for a long time, and she seemed to be a lot better now the engine was OK. We got up back of the Hooks Hard, out under the East Bank Head, and then came up inside of the Bank.

‘We got ashore alright - wasn't I glad, too - and a couple of days later we took the lifeboat to Shoreham for a refit. The landing craft that we went after had gone ashore at Dungeness, and the crew were in a pub at Hastings! I thought that was the end of that, but for months afterwards every time we got in a breeze of wind in the old RX 2, and she threw her lee side down, I could feel her going right over. I used to go hot and cold and shake like a leaf!’16

The crew of the lifeboat in the 1944 capsize were Ned Adams coxswain, Fred White second coxswain, Charlie Haste, Bill Martin, Dick Harffey, Tom Adams, Doug White, Jim Adams and Frank Edmunds.

The Second World War saw women play a more active part in the lifeboat service than at any time before then. During the war the absence of many men on war duties led to women becoming more prominent, and at Hastings, where hand-launching required many helpers, the lifeboat came to depend heavily on the women of the Old Town to get the boat afloat, although there was never a woman in the crew at that time.

After the War

On 14 September 1945 the Cyril and Lilian Bishop was launched in a strong south-westerly wind to help the naval sloop HMS Hastings, then paying a five-day courtesy call to the town. Thirty of her crew had gone ashore, but could not return to the ship in the rough seas, while the mayoress of Hastings, Mrs Lancelot Blackman, was stuck on board the vessel, unable to go ashore. The lifeboat returned the sailors in two trips to HMS Hastings, but Mrs Blackman extended her stay on board till the following day, when she was landed on Hastings Pier.

The war hero Field-Marshal Viscount Montgomery of Alamein visited Hastings on 8 March 1946, receiving a rousing reception from hundreds of people near the fishmarket, where the Cyril and Lilian Bishop and her crew were on display. Montgomery went on board the lifeboat, where he was greeted by Mr ‘Bunk’ Harffey, secretary of the Winkle Club, who presented him with a winkle.

Up until the start of the war in 1939 maroons had been fired to summon the crew to the lifeboat station, but this practice was suspended during the hostilities. Maroons were fired for the first time after the war on 9 April 1946, when the Fairlight Coastguard station reported seeing what appeared to be a fishing boat giving off a large amount of smoke. But no distressed vessel was found, and it was thought that a boat had simply been emitting much exhaust smoke.

The disabled Rye fishing smack Skylark was towed into Hastings harbour by the Cyril and Lilian Bishop on 13 May 1946. The engine of the 25ft boat broke down when she was off Pett Level and she started drifting out of control. The three crew were taken on board the lifeboat, and two lifeboatmen, Tim Adams and Frank Edmunds, went on the Skylark.

Two months later, a Hastings fishing boat broke down off Pett Level and had to be towed to the harbour. The Favourite RX 161 was caught in a sudden violent storm on Thursday 4 July 1946, and rainwater stopped her engine. The two crew of the 23 ft boat, built 1921, were returned safely to Hastings.

Hastings was going to have a new lifeboat and a new lifeboat house, it was announced at the AGM of the Hastings branch of the RNLI on 15 January 1947. Branch secretary Commander William Highfield RN said there was nothing wrong with the Cyril and Lilian Bishop, but the RNLI’s petrol-driven boats were being dispensed with in favour of diesel engines, which were more efficient. The new boat would be a ton heavier and a little broader, and it would have to have a new house to accommodate it, with better access to the sea. By early 1948 a site had been agreed with the fishermen and work started on drawing up plans.

Highfield congratulated the lifeboat crew on the fine work done during the war and the branch on the good financial results. ‘Today Hastings is a self-supporting station, and that is a thing which cannot be said of a good many towns at least as big as Hastings.’17

A Swedish sailing vessel, the cutter Polstjarnan, en route from Le Havre to Gothenburg, developed engine problems and tied up on Hastings Pier on 20 October 1947. She was boarded by police, who examined her papers, and as the crew were registered seamen they were allowed to go ashore. Two days later the Cyril and Lilian Bishop towed her to Rye for repairs.

In 1948 she gave help on three occasions. A 14ft sailing dinghy capsized three miles off Bulverhythe on 9 May. Another dinghy rescued the two crewmen, and the Cyril and Lilian Bishop helped all the people and both boats to get ashore. In the autumn, two Rye fishing boats were given help: The Susan Anne on 2 October, and the My Lassie on 13 November.

The Loss of the Pioneer

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop's most memorable service after the Second World War was the Pioneer tragedy in 1949. The Pioneer RX 255 was a nearly-new Hastings fishing boat, 24.5ft registered length, built at Eastbourne in 1946. She was owned by Jack and Tom Adams, the fish salesmen, and the crew on her last trip were Harry Muggridge (aged 49), brother of the late lifeboat coxswain Ned Muggridge; James ‘Jimmy’ Williams (27); and James ‘Jim’ Helsdown (55). They left Hastings early on Thursday 31 March 1949 to go trawling in Rye Bay. But later that day dense fog came down and the Pioneer lost her way as she came home.

At some time that evening, in calm weather, the Pioneer ran on to the Hooks Ledge reef under the cliffs at Fairlight Cove and sank in shallow water, leaving the three crew clinging to the wreck. Then followed one of the most tragic events in the recent history of the Hastings fishing industry. Just before midnight on Thursday the lifeboat and Coastguard shore rescue teams were called out in fog that cut visibility to less than 20 yards. The rescuers soon heard the three men and established their approximate position, 100-200 yards from the shore.

A Coastguard was lowered part-way down the cliff and managed to talk to the crew. But even though the searchers could hear the men, they still could not find them, and gradually the voices through the fog grew weaker and fainter as their strength ebbed away. Rocket lines were fired from the shore in the direction of the voices and the Cyril and Lilian Bishop probed the rocks, yet still the three could not be found. At 2.20am they were heard for the last time. When dawn broke at 5.00 the ebbing tide revealed the Pioneer, with most of her bottom gone. Muggridge's body was found beside the boat, next to the broken mizzen mast, his feet entangled in the rigging. A few feet away lay Williams. A reporter from the local paper who witnessed the scene described it as a ‘harrowing experience’.18 Helsdown's body was carried by currents to Bexhill, where it was found some hours later.

The inquest was held on Monday 4 April in a bungalow at Fairlight Cove within sight of the Hooks Ledge rocks. The coroner, Mr FC Sheppard, recording a verdict of ‘accidentally drowned’, said ‘All three were very experienced seamen, and the wreck would not have happened but for the extraordinarily thick fog, in which all sense of direction must have been lost.’19 The Pioneer was salvaged and brought back to Hastings, but as she was now thought to be an unlucky boat she was broken up rather than repaired.

The loss of the Pioneer and her crew was a terrible shock for the Hastings fishing community. It was the sort of tragedy that could so easily happen at sea but had luckily been rare at Hastings. Widespread sympathy was felt for the bereaved, and the fishermen, supported by Hastings Council, set up the Hastings Fishermens’ Disaster Fund to help the widows and dependents of the three men. When the very successful fund closed in early June 1949, the total collected was £1,728.20

After the Pioneer

A fortnight after the Pioneer tragedy, the AGM of the local branch of the RNLI on 13 April 1949 was told that the long-awaited new lifeboat should arrive in early 1950, and work on the new lifeboat house would start in a few weeks.

The tireless lifeboat secretary Commander William Highfield, ex-RN, had first approached Hastings Council for a new boathouse site in December, 1945. The lifeboat's launching had been hindered by the building of the boating lake between the lifeboat house and the sea in 1933, and discussions took place during 1946 to find a site nearer the harbour wall, then regarded as the best launching place. In January 1947 Commander Highfield revealed that Hastings would soon be receiving a new diesel-engined lifeboat, safer and more reliable than those with petrol engines. Hastings Council, however, refused to agree a site for the boathouse until a legal agreement with the fishermen about their rights over the beach had been signed in 1947, and this delay led to the original new lifeboat being sent elsewhere by the RNLI.

Commander Highfield announced in May 1948 that a site near the harbour had been settled at last. He said it was not perfect, but would suffice. The foundations for the new house were laid in July 1949, at the same time as the new Hastings lifeboat-to-be was being built at Messrs Groves and Gutteridge's yard at Cowes. The new lifeboat house, which was replaced in 1995 with the current building, had to be prefabricated because of the unstable nature of the beach. Construction was finished in late autumn, 1949. In September 1949 Commander Highfield stood down as secretary, after 16 years service, and was awarded a vellum by RNLI for the quality of his work. He was succeeded by Cllr George Steel.

In the summer of 1949 the Cyril and Lilian Bishop had a series of small-scale launches. The fishing boat My Lassie RX 202 broke down off Pett Level on 1 July because of engine failure. She lay at anchor for 22 hours before the crew’s distress signals were spotted by the Fairlight Coastguard. They notified the Cyril and Lilian Bishop, which towed her back to Hastings.

Over the August bank holiday weekend the lifeboat was called out twice. The first was on Saturday 30 July for a small sailing boat off Winchelsea Beach, which was towed to Hastings. The second was on the Sunday evening for a dinghy seen adrift about two miles out to sea, which turned out to have a yacht’s towed dinghy which had broken adrift. On 6 August the Cyril and Lilian Bishop towed a dismasted yacht, the Makrojak, with a crew of four into the shelter of Hastings harbour. But owing to its draught the yacht could not be pulled up the beach, so later that day a heavy motor vessel towed her to Shoreham.

On 22 September the Hastings fishing boat Ena RX 64 was seen flying a distress signal off St Leonards Pier after her engine had broken down. Watched by hundreds of holidaymakers, the lifeboat was launched in seven minutes, and soon had the boat in tow and back on shore. On board were the skipper Ron Peters and his mate Jack Jenner. The next launch was on 16 October 1949 to help the Muriel L London, an ex-RAF motor launch converted as a cabin cruiser. She had anchored east of the harbour, but dragged her anchor when the weather turned rough. The crew flashed distress signals to the Coastguard, and the lifeboat towed her to Rye Harbour.

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop was moved to her new house on Monday 5 December 1949. This was the last time that the old wheeled carriage was used, for the lifeboat could now sit on rollers at floor level in the new house, and could be pulled across the beach on troes (skids). There was to be no more hauling the lifeboat along the seafront; since 1949 the lifeboats have been launched on either the east or west sides of the harbour, depending on the wind. An electric capstan inside the house heaved the lifeboat up the beach and into the building. A turntable outside the folding doors turned the boat round before it was put away, so that launches could be made bow first.

The attractive old grey-stone Victorian lifeboat house next to the boating lake was rented out to the sea scouts in 1950. When they gave up the lease in June, 1959, the Council refused to consider new tenants, and demolished the building that December. No reason was given for this unnecessarily hasty action. It proved convenient for the Council soon after, however, as it allowed them to rebuild the seafront between Marine Parade and the Bourne when finance suddenly became available in 1963.

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop’s first launch from the new lifeboat house was on 26 December 1949. A call was received from the steamer Yarvick which was reported to be disabled 12 miles south-west of Hastings. There was a gale blowing, and at 5.30am the lifeboat was thrown back onto the beach three times before she took to the water. But just as that was achieved, a message was received saying that she was not required.

There was another false alarm on 2 February 1950, when a Brighton fishing boat was reported in distress off Dungeness. The Hastings and Dungeness lifeboats were launched, but the Cyril and Lilian Bishop was recalled soon after being launched, as the Dungeness lifeboat had towed the vessel into Rye Harbour. Sixteen days later, on the evening of 18 February, flares and flashing lights were seen under the cliff at Ecclesbourne Glen, so the lifeboat was launched, only to find two fishermen with a motor boat looking for prawns!

Since 1950

The new Hastings lifeboat replacing the Cyril and Lilian Bishop was launched at Cowes in early January 1950. After three months fitting out and trials she reached Hastings on 19 March and was greeted by a crowd of hundreds of people. The new boat immediately took over from the Cyril and Lilian Bishop, which left Hastings later that same day and went to Cowes to be placed in reserve.

The new lifeboat was called the MTC after the wartime Mechanised (or Motor) Transport Corps, a section of which, the Trained Women Drivers' Association, had donated its funds to the RNLI on its disbandment. The MTC cost £13,000 and the Association contributed £9,800 of this. The MTC was a self-righting version of the Liverpool type of lifeboat, most of which were not self-righting. She was 35½ feet long and ten feet wide, similar dimensions to her predecessor. She was twin-screwed, with two 18 hp engines producing a top speed of 7½ knots and a range of 115 miles. But the engines were petrol-driven, rather than diesel, as had originally been planned. The boat could self-right in about 12 seconds and displaced about 8½ tons.

The MTC had a crew of seven, and could take 30 people on board in rough weather. Ned ‘Wintry’ Adams, the last coxswain of the Cyril and Lilian Bishop, was coxswain of the MTC until he retired in 1952.

Although the MTC was a motor-driven vessel, her appearance still owed much to the old pulling-and-sailing craft. She had the basic rowing lifeboat profile: high bow and stern, sweeping down close to the sea amidships, with covered in bow and stern to provide buoyancy. The MTC was the first Hastings lifeboat not to use any sail power, however, and more space was given over to the central cabin providing shelter and access to the engines. She was officially christened MTC on 19 July 1950.

The Cyril and Lilian Bishop was later sold by the RNLI and could easily have disappeared without trace if it had not been for an odd coincidence in 1962. That August a former Hastings man, who had witnessed the arrival at Hastings of the Cyril and Lilian Bishop in 1931 and her return from Dunkirk in 1940, was travelling in Scotland when he came across the old lifeboat. The Cyril and Lilian Bishop had been converted into a pleasure craft, he believed, and the boat was lying alongside a stone quay in the Sound of Mull, a ‘lonely and sorry sight'.21 She had broken down and been towed to the quay, where the owner had left her and not returned.

In 1993 the Dunkirk Little Ships Restoration Trust was founded to save ‘Little Ships’ in danger of destruction, and the Cyril and Lilian Bishop was the first boat it aimed at rescuing.22 The trust said she had been sold in 1950 as a fishing vessel and went to the west coast of Scotland, where Mr Arra Fletcher bought her in 1976. ‘He renamed her Lindy Lou after his daughter, and brought her to the free port of Askaig on the Isle of Islay. There, she earned fame when her owner fought a battle against authority in 1980.

‘The Duke of Kent was due to visit the island, and the powers-that-be wanted the old boat removed from the harbour because of complaints that her time and weather-worn appearance might offend the royal eye. Arra Fletcher, who had painted her and dressed her overall, and whose ancestors arrived in Islay centuries ago, occupied his ship to defend the islanders’ right to free use of the harbour. He won the day when his case was taken up by the press and TV after letters of protest to 10 Downing Street and Buckingham Palace, and a flood of sympathetic messages from all over Britain.’23

Mr Ernest Spray, of Parker Road, Hastings, told the Hastings Observer that ‘Some time later, while she was in harbour and tied up to another fishing boat, the fishing boat sank and took our old lifeboat down with her! During this time on the bottom, the tides filled her with mud and sediment a very sad state of affairs.

‘Happily, in 1993 the boat was rescued by an arrangement between the Dunkirk Little Ships Restoration Trust, a Mr Simon Evans - who has his own boatyard in France - and who agreed to take immediate charge of the boat. The Landing Craft Division of the Army sent a landing craft to Askaig and, after three attempts, finally managed to extract her from the beach. The Army then brought her to their base at Marchwood, near Southampton, where she was loaded on to Mr Evans’ transporter and brought directly to his boatyard near Sens, France.’24 Mr Evans, a British boatbuilder and lifeboat enthusiast, owns the Evans Marine Boatyard on the River Yonne at Migennes, south-east of Paris.

Mr Spray said the Cyril and Lilian Bishop had joined many other lifeboats that Mr Evans had. ‘He is now in the process of restoring our Hastings boat to its former glory. She was in a sorry state when she arrived, being just a shell without decking or wheelhouse - but she did have three tons of Scottish mud! Mr Evans has now completed the re-decking and has built a new wheel shelter, but there is still plenty more restoration work to be done.’

On their own initiative, two Hastings men of local fishing families, DeeDay White and John ‘Tush’ Hamilton, purchased the Cyril and Lilian Bishop from Mr Evans in 2016 and brought her back to Hastings (on a lorry) on Friday 1 July.

DeeDay (real name) is so-called because he was born on D-Day, 6 June 1944, when Allied troops successfully invaded Normandy. Many members of his family have been involved with the Hastings lifeboats over the years, including his father Bert and brother Bert. DeeDay runs an eclectic shop of many things in Courthouse Street, and over the years has put up many permanent outdoor exhibits of the fishing community around the Old Town.

Tush’s father, also called Tush Hamilton, was a crewman on the Charles Arkcoll II, the Hastings lifeboat immediately before the Cyril and Lilian Bishop. Around 1960, when he was a teenager, Tush Jnr became a member of the reserve crew of the Hastings lifeboat. In the late 1960s he and his wife Pat bought a fish shop in the High Street, so he could not become a lifeboat crewman. Instead Tush became driver of the tractor used for manoeuvring the lifeboat, followed by being head launcher of the lifeboat from 2002 until he retired in 2009. He now runs the famous stall in Rock-a-Nore Road selling fish rolls.

The cost of buying and restoring the Cyril and Lilian Bishop is many thousands of pounds, and preserving her in the coming years will also be expensive. If you would like to help pay the bills, you can make a cheque payable to The Macbean & Bishop Trust and send it to the treasurer at 4 All Saints Crescent, Hastings TN35 5PD, or pay in at any Santander Bank. Or you can go via internet banking: sort code 090128, account 49444310.

1 Hastings Lifeboat History, by RNLI

2 The Engineer, 29 November 1929

3 Plans of the Cyril and Lilian Bishop are at the National Maritime Museum, Ref Box JSWB0160

4 Plans of the Cecil and Lilian Philpott are also at the NMM, Ref Box JSWB0160

5 Hastings Observer 2/5/1931

6 Hastings Observer 22/8/1931

7 Hastings Observer 4/6/1938

8 Hastings Observer 18/1/1947

9 Dunkirk, by AD Divine, p133

10 Kevin Boorman, interviewed by Steve Peak, June 2016

11 Bill Terrell, interviewed by Steve Peak, December 1984

12 Hastings Observer 8/1/1944 and 22/1/1944

13 Hastings Observer 2/11/1940

14 Hastings Observer 7/9/1940

15 Charlie Haste, interviewed by Steve Peak, December 1983

16 Ibid

17 Hastings Observer 18/1/1947

18 Hastings Observer 2/4/1949

19 Hastings Observer 9/4/1949

20 Hastings Observer 4/6/1949

21 Hastings Observer 25/8/1962

22 http://www.dlsrt.org.uk

23 Dunkirk Little Ships Restoration Trust

24 Hastings Observer, letters page, 28/3/2008

Sources

Benbow, Tim - Operation Dynamo: The Evacuation from Dunkirk, Helion & Co, 2016.

Blaxland, Gregory - Destination Dunkirk, 1973

Brann, Christian - The Little Ships of Dunkirk, Collectors Books, 1989

Divine, AD - Dunkirk, Faber & Faber, 1945

Dunkirk Evacuation - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunkirk_evacuation

Dunkirk Little Ships Restoration Trust - www.dlsrt.org.uk

Ellis, Major LF - The War in France and Flanders 1939-40, HMSO, 1954

Evans Marine International - www.evans-marine.fr

Gardner, WJR - The Evacuation from Dunkirk, Frank Cass for the MoD, 2000. Complete

Howarth, Patrick - Lifeboat: In Dangers Hour, Hamlyn, 1981

J Samuel White & Co, shipbuilder - www.gracesguide.co.uk/J._Samuel_White_and_Co

Leach, Nicholas - The Lifeboat Service in England: The South Coast

Little Ships of Dunkirk - https://en.wiki2.org/wiki/Little_ships_of_Dunkirk

Lord, Walter - The Miracle of Dunkirk, Wordsworth Editions, 1998

Mace, Martin - They Also Served - The Story of Sussex Lifeboats at War, Historic Military

Morris, Jeff - The Story of the Hastings Lifeboats, Lifeboats Enthusiasts’ Society, 2000

National Historic Ships: Cecil and Lilian Philpot -

Peak, Steve - Fishermen of Hastings, SpeaksBooks, 2005

Plummer, Russell - The Ships that Saved an Army, Patrick Stephens Ltd, 1990

Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) - www.RNLI.org

RNLI - Hastings Lifeboat History, recent RNLI pamphlet

RNLI, in World Public Library - http://www.worldlibrary.org/articles/rnli

The Evacuation from Dunkirk: Despatch by Admiralty on 18 June 1940, in London Gazette

Vince, Charles - Storm on the Waters: The Story of the Lifeboat Service in the War

Warner, Oliver - The Lifeboat Service, Cassell, 1974

Any additions/amendments welcome; contact via