Three ancient fairs were held every year in Hastings until they were brought to an end by the local establishment in the 1860s and ‘70s because of the ‘trouble’ they had been causing.

These fairs were combined funfairs, trading markets and social meeting places, where people could meet friends, conduct some business and have a enjoyable time eating, drinking, playing games and watching theatre shows.

The first annual fair on the calendar was the ‘Whit-Tuesday Fair’, which probably originated from pagan celebrations of the start of summer. It was usually at the end of May, but did not have a fixed date as it took place on the Tuesday immediately following Whit Sunday - the seventh Sunday after Easter Sunday, which itself was of a variable date in late March/April. Town records say that in 1656 an order to restrain immoderate drinking was to start “three days after Whitsun Faire”.[i]

The ‘Winter Fair’ or ‘Town Fair’ took place every November 23 and 24. The 23rd was St Clements Day, being dedicated to Pope Clement, the patron saint of blacksmiths. It attracted many people from out of town, and in 1582 the bailiff of Hastings wrote to the mayor of Rye to inform him that, because of the plague then raging in London, the town would not hold the fair for fear of infection.

Both these fairs were held on the beach in front of the Old Town, the main site of the town of Hastings from the 12th century, but the third annual fair, the ‘Rock Fair’, may have been even older.

The Rock Fair

The Rock Fair was held on July 26 and 27 every year, and in 19th century (and possibly before then) was the biggest of the three fairs, with large numbers of all classes of people taking part. The reason for having it on those dates is unknown, but it may have been because by late July the annual mackerel-catching season would have ended, usually giving the fishermen some extra income which could be spent at the fair.

The Fair was organised by Hastings Council in the 18th century, with town records showing that the Council at that time laid out lines on the ground marking its area.

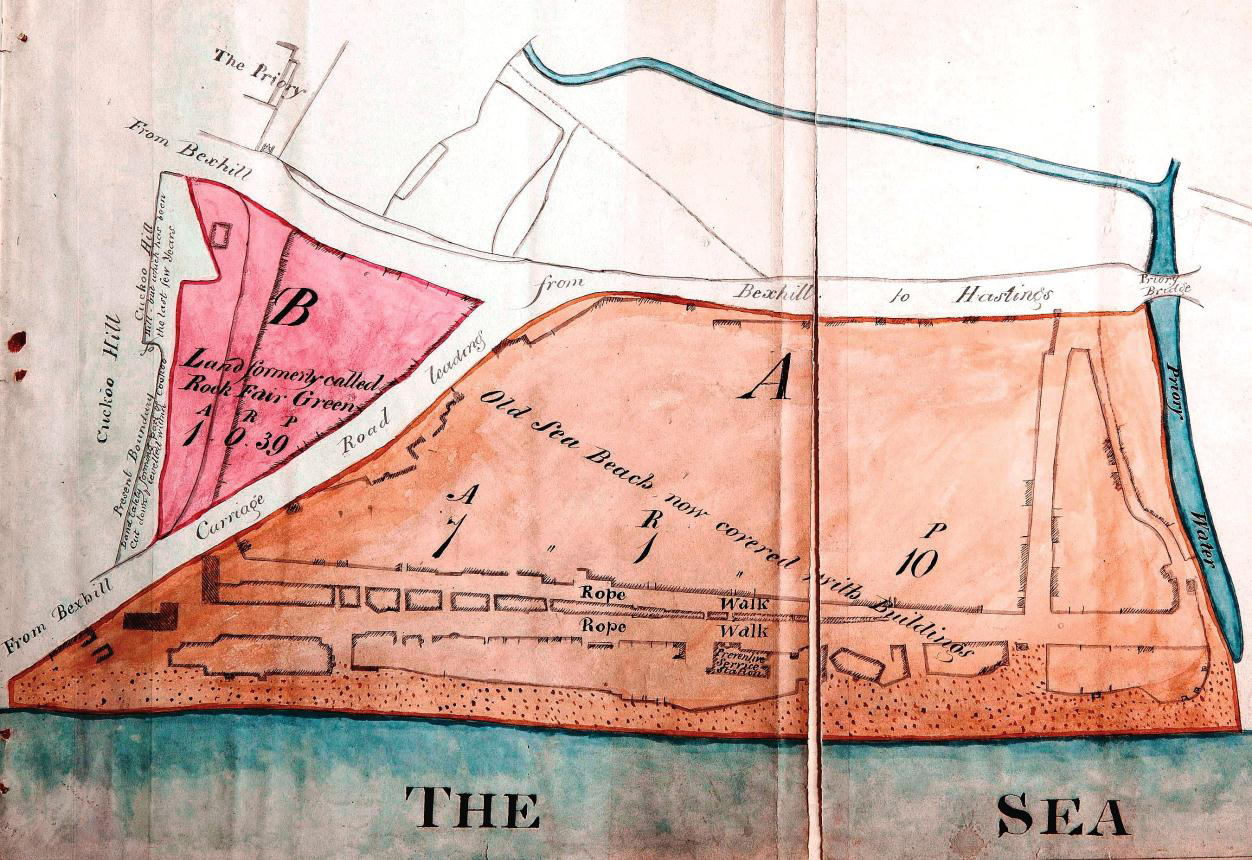

Victorian local historian Thomas Brett said that until 1822 the Rock Fair had always been held on the part of the ‘America Ground’ where today Claremont, Trinity Street, Robertson Street form a triangle.[ii] An 1827 government map of the America Ground describes the Fair’s location as ‘Land formerly called Rock Fair Green’. The Green abutted the promontory of White Rock, the probable Saxon location of the town of Hastings, and it is most likely that the fair took its name from that headland.

In the early 1820s the Ground had started being heavily developed as a housing and industrial estate, often by squatters, and in 1822 much of the Rock Fair Green was taken over by the prominent Breeds family, forcing the annual Fair to find an alternative site.

The Fair was a very popular mixture of fun, games and social get-togethers, with many stalls supplying, food, drink and games. It attracted large numbers of people from both the town and the surrounding countryside. But also by the early 1820s the fair was becoming more problematic, as a Hastings man recalled: “It resembled an ordinary fair, but a vast amount of gambling took place with halfpence, and fishermen often staked, and lost, their boats, nets and other appliances.”[iii]

The Rock Fair in 1811 on what became known as the America Ground. Cambridge Road on left

The Rock Fair in 1811 on what became known as the America Ground. Cambridge Road on left

In 1823, having been forced to relocate, the Fair was held nearby, probably in a Priory Farm field, where Cambridge Road and Priory Street are now (Cambridge Road was then much lower, and one could walk on almost flat ground from Claremont through to the farm, which was where Cambridge Gardens is today).[i] This area was to become its main home in following years.

Commenting on the 1823 fair, the Sussex Advertiser of 4 August 1823 reported that “In consequence of the quantity of rain which had fallen, the intended spot for gaiety and ludicrous exhibition had a complete surface of mire and water yet the lads and lasses from town and country were not deterred from encountering all the difficulties and disasters arising from the inclemency of the weather, and boldly displayed their blooming, healthy countenance, robed in white gowns, and dashing coloured ribbons, best hats and holiday attire, wading through the scene of action, unaided by mud boots, and inundated with celestial dews, laughing at each other’s bespattered appearance, and evidently enjoying the fun. Fortunately the fair terminated without any accidents, except a few discoloured eyes, and bruises, from pugilistic strifes.”

The 1825 Fair had a “very lively appearance ... with numerous groups of fashionable visitants interspersed with country lads and lasses in their gayest clothing, and all was mirth and merriment.”[ii]

In 1827 the Advertiser said “Our Rock Fair, which is now held in a field near the road leading to the Priory, nigh to a beautiful and picturesque part of the country, was well attended by the holiday folk. The favourable state of the weather added not a little to the bustle of the occasion, and vehicles of every description were in constant requisition. Men, women and children, of all classes and ages, seemed determined to make themselves happy, amid the display of mountebanks and music, champagne and cherry bounce, gin and gingerbread, and all the fun, frolic and glee usual upon such occasions.”[iii]

The 1831 Fair was “extremely gay, and crowded with holiday folk, from the town and adjacent places.”[iv]

The America Ground in 1827. The Carriage Road is now Robertson Street

The America Ground in 1827. The Carriage Road is now Robertson Street

The Fair Problems

By the mid-1830s the fair was encouraging gambling and drunkenness on an increasing scale, but initially its real crime, as far as Hastings Council was concerned, was that local traders (heavily represented on the Council) suffered a serious loss of business while the fair was taking place.

The Government took possession of the America Ground in 1835 and removed all its occupants and buildings, thereby giving the Council an opportunity to redevelop the adjoining ground where the Fair was being held.

As a result the Council in 1836 considered building a harbour on the America Ground, and justified choosing that location in a statement: “Having been formerly derelict and unenclosed, and served as a place for Hastings people to play at cricket and other games, and served for fishermen drying nets; that a public fair was held there from time immemorial; that no owner having asserted or maintained any claim to the land.”[i]

While drawing up plans for a harbour (which came to nothing), Hastings Council also set up a committee in 1837 to “enquire into the circumstances of Rock Fair, with a view to it being abolished or to render it more useful and profitable to the town without interfering with rational amusements.”[ii]

But this was also unsuccessful, and in 1846, as the Fair became increasingly rowdy, the Council tried to quash it altogether by issuing an official-looking notice saying that the Fair “will cease to be held” because it was “objectionable and of no public benefit”. Many local landowners also agreed not to allow it on their property. But the Rock Fair continued unabated, because by the mid-1840s Hastings had entered a period of sustained economic growth and expansion.

The local fishing industry was benefitting from the national railway network that was being built, as this opened up big new markets for their catches, and the Rock Fair was “the fishermen's holiday, the only time in the year when all the fishermen put on their best clothes”.[iii] In the mid-1840s it was even more popular than before, attracting large crowds of people of all ages to enjoy the “medley of gingerbread nuts and dolls, Middleton [a theatre] and gypsies, peep-shows and penny trumpets, dwarves and giants, gangs and cheapjacks, drinking and dancing”.[iv]

With better incomes, the fishermen and the other working class people living in the boom-towns of Hastings and St Leonards spent more of their new money at the Rock Fair on the proletarian pleasures of gambling and alcohol. But the large crowds of merrymakers were increasingly distasteful to the new generation of middle-class Victorian abstainers and shopkeepers.

The Council’s problems with the Fair came to a head in the late 1840s when the Hastings area railway system was being built, and 3,000 hard-working and hard-drinking navvies moved into the town. The Fair had remained in the Priory Farm area for many years, but was forced to move out because of the siting of the railway station there. In 1850 the Fair was reported as moving onto the top of White Rock, between today’s White Rock Gardens and Cambridge Road, part of Wastel Brisco’s large estate.

The Fair was described as a “grievous moral pest” by a letter-writer in the Hastings News of 27 July 1849. “Efforts have been made, both private and magisterial, to abolish it, and yet it lives.” The correspondent complained about the “wholesale debaucheries, the disgraceful riots of every year’s fair”. Another letter writer in that edition urged the authorities to clear the fair before the evening of the following day, because that was the Saturday when the thousands of navvies were going to be paid their fortnightly wages.

The following year, 1850, the News reported that the Fair’s “especial patrons consisted of the most riotous and dissolute characters in the neighbourhood, the [railway] navvies forming a large proportion. The authorities withheld their countenance from the concern so that the parties who thought fit to visit the scene had it all to themselves. Fighting and drunkenness formed the substance of the proceedings.” It was just as bad in 1851: “The amount of dissipation was quite sufficient to excite and to justify a desire that this excuse for riot and profligacy should be suppressed.”[v]

The “annual saturnalia” of the Fair on White Rock in 1852 had constables in private clothes in attendance, on the lookout for gambling, which the mayor had ruled unlawful.[vi]

The navvies moved on from 1852, but the Fair remained a problem. It entered its last phase in 1858, when building work at White Rock and hostility from the owner of the ground, Wastel Brisco, forced it to move to farmland where Manor Road is today. This was part of Mount Pleasant Farm, owned by Henry Wyatt, a retired London brewer who had been in conflict with Hastings Council for trying to block footpaths on his extensive property.

Thomas Brett in the mid-1880s recalled that: “The once famous annual festival, with its fancy stalls, fruit stalls, gingerbread stalls, oyster stalls, Middleton’s marionettes, Richardson’s theatricals, publican’s booths, merry-go-rounds, glass-blowing and wax-works, together with giants, dwarfs and other monstrosities, was driven farther afield.”[vii]

Brett said that in 1858 “it was hoped that this degenerated Fair had died out for the want of a place to hold it.”[viii] The News said “The Fair had gotten to be neither useful nor ornamental, but simply a rendezvous for the dissipated and vicious.”[ix]

But the Fair lived on, and in July 1860 the local magistrates discussed “this abomination”, and whether it could be prosecuted for some offence relating to the sale of alcohol.[x] The law was unclear, however, so the Fair proceeded as usual that year. Twelve months later, in July 1861, the magistrates took a harder line, issuing a notice that all parties selling “excisable liquors” at the “illegal fair” would be prosecuted.[xi] But the Fair promoters ignored the notice, claiming they had received the sanction of the excise authorities. That was not true, however, and after the Fair took place the Board of Inland Revenue threatened to take proceedings - but it was too late to find the offenders.

The Rock Fair’s Two Obituaries

The Hastings News in July 1861 had thought that the Rock Fair would be permanently suppressed by the magistrates’ liquor notice, so on the first day of the Fair, 26 July, the newspaper’s editor published what he hoped would be the Fair’s obituary. But his hopes were dashed, for the Fair survived until 1864, probably its last year. In 1865 Mr Whyatt refused the use of his land for the Fair, probably because of the large amount of house-building then taking place in that area. So in July 1865 the News could publish its second death notice of the Rock Fair.

The premature 1861 obituary highlighted just how unhappy the virtuous middle class Victorians, who once supported the Rock Fair, had become with it. The News said in 1861:

“However necessary ‘fairs’ might once have been, in another state of society, the use of them, at least in this neighbourhood, has passed away. For a long time, indeed, after the need of them had ceased to exist, many old-fashioned respectable people helped to keep them up, as mementos of those ‘good old times’ with which they associated, with a natural and pardonable weakness, everything prosperous and pleasant. This was the case with that time-honoured institution of Hastings, called ‘Rock Fair’.

“In the early days of the present generation, this yearly gathering for gingerbread and fun … was encouraged by the better-class of the residents, whose families, decked in their ‘Sunday best’, marched regularly to the Fair, afternoon and evening, as a matter of course; returning home, however, before darkness set in. Those were good days and most orderly times - the patriarchs of our own days being witnesses. … Let us be content to regard this once-venerable means of popular amusement as a dream of the past. As a joy of the present or a hope of the future it can be ours no longer. … Rock Fair is dead. Driven from its accustomed place of ‘holding’, where alone it could claim a legal life, it has for years led a kind of vagrant existence: sheltered sometimes by a professed regard for the amusement of the poor, and always by a real regard for the interests of beer-sellers, and vegetating, rather than living, as a loathsome excrescence on the slumbering form of the ‘body politic’.

“Its day is over - its home is taken from it by the gentle violence of social progress - its work is done. … On strange ground, and arrayed in strange fashion, has a spectral resemblance of old Rock Fair been for years palmed-off upon ignorance and folly as the veritable friend of our youth. Around the foul feet of this specter have orgies been held, and bacchanalian rites observed, that would have made the baseness of any Pagan immorality look lustrous with social purity by their side. We are glad to find that this spurious copy, this pretended but unacknowledged offspring, of the Rock Fair of our childhood, is to offend us no more within the limits of the borough.

“The magistrates have wisely resolved to wash their hands of the consequences of this abominable mimicry of the recreations of olden time. If they wanted work for themselves and the police, - if they wanted to encourage drunkenness among tipplers and to help thoughtless youngsters to become drunkards, - if they wanted to harbour pick-pockets, and to countenance the confirmed profligate, - if they would make virtue harder and vice easier to the undecided and ill-guarded youth, - they would give their moral support to these and similar illegal places of unregulated amusement. But we are happy to know that our-magistrates do not wish this. …

“We hope that everybody who has the least respect for his own moral character, - every man who regards public virtue as a good and domestic peace as a blessing, - will support this determination of the magistrates to suppress a social nuisance and a moral pest which ought no longer to disgrace the suburbs of a civilized town in the nineteenth century. … Positive disgrace and ruin have overtaken scores of young people of both sexes whose greatest fault, before they knew this wretched shadow of a fair, was want of thought: but whose character since has been too bad to be pictured here: and whose end will be - God alone knows what.”[xii]

The nearly-dead 1861 Rock Fair was reported as actually being a large event, but from then on it declined, and the last one of any size seems to have been held in 1864, when the borough magistrates posted a notice saying that the police would take action against all people selling excisable liquor there. There are no reports of it in later years.

So on 28 July 1865 the News published its second obituary. This echoed the 1861 denunciation of the Fair, saying that in the last few years there had been “a large increase of immorality in connection with it; and we wonder how anybody who knows how much drunkenness and debauchery have lately characterised this fair, can plead for its continuance on any ground whatever. The plea that the poor want amusement does not avail here; unless it be contended that such amusement should be sought in the company of the most abandoned of both sexes, and in the midst of the most revolting excesses.

“Very few of the respectable poor would be seen there; and of those who do go, the greater number have to rue it. We are glad then to learn that this fair has at last died out. ... A visit to Rock Fair has cost many a man and woman the hard earnings of several days, and sometimes the character of a life.”[xiii]

The Fair may have been stopped, but it lingered on in the memories of local people. On 1 August 1871, fisherman Daniel Thomas was fined a shilling (5p) by Hastings magistrates for throwing some sacking at an “Evangelist” who was preaching at the fishmarket on 25 July. Thomas said he and some other fishermen had been “sky-larking”, and it was done accidentally. His defence was that “it was the first day of Rock Fair.” A magistrate thought the “spree” was in lieu of Rock Fair, now they had “lost it”.[xiv]

The Rock Fair in the early 19th century had been a wide-ranging, mainly working class, social event and market, which the local establishment at that time felt able to patronise while the workers more-or-less behaved themselves. But as the town began rapid expansion in the late 1850s, and the Fair’s market role declined, the Fair attracted many members of the increasingly vigorous labouring class who had come into the town to build the new houses and shops, and their ‘bacchanalian’ behaviour and culture conflicted with the increasingly abstemious attitudes of their employers and the local authority.

The End of the Town Fairs

Having quashed in 1864 the ‘loathsome excrescence’ known as the Rock Fair, Hastings Council turned its attention to the town’s two other annual celebrations, the Whit-Tuesday Fair (also sometimes called the Whitsun Town Fair) and the November Town Fair. These had both been events primarily for the fishermen, on a smaller scale than the Rock Fair in the 19th century, and possibly before then. Like the Rock Fair, a key reason for the original running of the Town Fairs was as market-places, but this function was largely taken over by the increasing number of shops in the early Victorian years.

The traditional site of the two fairs was at the bottom of High Street, where the small car park is today. In 1851 the November Town Fair “comprised as usual a few gingerbread and peddlers’ stalls”, but on that occasion some 70 horses no longer needed for the works on the new railway were sold and gave the fair unusual importance.[xv] But the fair carried on declining, and in 1853 was described as “a poor assembly of peddler’s stalls and travelling shows”.[xvi]

(Gingerbread, a feature of all the town’s fairs, gets its name from the root ‘ginger’, which has long been associated with health benefits and holistic medicine. In the Middle Ages ginger was also discovered to have a preservative effect when added to biscuits, pastries and bread. From the 15th century onwards gingerbread (bread with ginger), flavoured with treacle, was a fairground delicacy throughout western Europe. In England gingerbread often came as biscuits shaped as men, a form attributed to Queen Elizabeth I, who served such figurines to foreign dignitaries. Gingerbread was widely used at fairs for many centuries because it was one of the few types of preserved food then available, and gingerbread biscuits could be carried easily.)

Hastings Council began bringing to an end the two surviving fairs by building a new retail fishmarket on their usual High Street site in 1870. The Hastings Chronicle of 30 November 1870 reported: “The Town Fair: This time-honoured [November] institution, consisting at the most of two or three gingerbread stalls, about the same number of peep-shows, a merry-go-round, a shooting ‘gallery’ and a ‘cheap John’ [hawker], was again brought under public notice on Wednesday and Thursday last. The new Fishmarket being built on a greater portion of the site on which the fair has hitherto been held, and the fishing boats being drawn up as far as the roadway in order to avoid damage by the high tides, the fair proprietors had very little space on which to display their attractions.

“Fortunately the demands for space were proportionately limited, and there were signs that the abomination of a bye-gone age is becoming ‘small by degrees and beautifully less’. ... The sooner the institution is abolished the better.”

A petition was launched against the November Town Fair, and the editor of the Hastings Observer fully supported the campaign: “Town Fair is an abominable nuisance to all respectable people in and about the neighbourhood, and a cause of dishonesty, drunkenness, and kindred vices and crimes in others. Children will steal, for boys and girls will dissipate their hard-won earnings on trash; men and women will get drunk over the glories of the Fair. For two days in every November the neighbourhood of the fishmarket is a perfect saturnalia with its shows and noise and bad characters.

“The Fair, it is true, has been held from time immemorial; but ... it has never been an ornament, and of late years it has become a disgrace, not only attracting and harboring persons of bad character and ill repute, but deterring respectable people from frequenting that part of the town in which it held.”[xvii]

The last Whit-Tuesday Fair took place in late May 1871. The Hastings News said the fair had “nearly disappeared. This year it was only represented by about half a dozen small stalls for the sale of gingerbread and nuts.”[xviii]

Hastings Council voted in January 1872 to actually abolish both of the town fairs. Cllr Poole told the January Council meeting that “he was sure the inhabitants - especially of that part of the town - would be very glad to have done away with what was an abominable nuisance; and to prevent the assemblage of a class of people who were no credit to the town or anybody else.”[xix] Both the town fairs had been established under the protection of a Royal Charter many centuries earlier, so the Council had to obtain the Secretary of State's consent, which was forthcoming in March that year.

The South Eastern Advertiser published a letter from “A Snarler” who thought that the amusements at the fairs were “adapted to fire simple natures which have just emerged from the primitive or barbarous stage of existence”.[xx]

Ironically, in August 1872, just five months after leading members of the Hastings establishment had finally managed to do away with the last of the town’s ancient festive fairs, the powers-that-be themselves launched a new and even more popular form of mass entertainment, merriment and imbibing: Hastings Pier.

Notes

[i] Brett, History, vol 2, p 138

[ii] Brett, History, vol 2, p 189

[iii] Hastings News, 27 July 1855

[iv] Hastings News, 1 August 1856

[v] Hastings News, 1 August 1851

[vi] Hastings News, 30 July 1852

[vii] Brett, Historic Biographies, vol 2, p 158

[viii] Brett, History, vol 7, p 78-9

[ix] Hastings News, 23 July 1858

[x] Hastings News, 27 July 1860

[xi] Hastings Chronicle, 31 July 1861

[xii] Hastings News, 26 July 1861

[xiii] Hastings News, 28 July 1865

[xiv] Hastings Observer, 5 August 1871

[xv] Hastings News, 28 November 1851

[xvi] Hastings News, 25 November 1853

[xvii] Hastings Observer, 2 December 1871

[xviii] Hastings News, 2 June 1871

[xix] Hastings News, 12 January 1872

[xx] South Eastern Advertiser, 17 February 1872