This is a new biography of Robert Tressell, author of the famous and influential socialist novel The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists. It has been put together by Steve Peak,

who used the resources listed at the end of this publication, plus his general knowledge of Mugsborough – Hastings and St Leonards – where he has lived most of his life. The starting place has been Fred Ball’s invaluable biography ‘One of the Damned‘, and in what follows all ‘Ball’ references and quotes are from his 1979 edition of that book, unless stated otherwise. ‘The RTP’ means ‘The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists’, and quotes from it are from the 1993 Flamingo edition.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Early Years

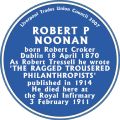

There is little evidence about Tressell’s earliest years. He came from a complex family background, details of which he did not pass on to his daughter Kathleen. Ball relied on a birth certificate, which stated that a Robert Croker was born on 18 April 1870 at 37 Wexford Street, Dublin, being the son of Samuel Croker, a “pensioner”, and Mary Croker, nee Noonan. [Ball 219]

Ball eventually decided that Tressell was the illegitimate son of Sir Samuel Croker, a “man of some substance”, who had two “wives”: His legal wife was Jane Usher (surname unknown), whom he married in 1827 and had five children: Annie, Jane, Arthur, John and Samuel. Later in life Sir Samuel had a “Liaison Lady”, Mary Noonan, whom he did not marry. That couple’s known children, apart from Robert, were Adelaide, Ellie and Mary Jane. Sir Samuel, born 1790/1, had been an inspector in the Royal Irish Constabulary, and then a resident magistrate until 1843. He was a well-educated Irishman, of Dublin. Sir Samuel was apparently not a Catholic, although Robert may have been brought up as one. He died about 1875/6. [Ball 219-24, 243-44]

But was Sir Samuel really the father; he would have been about 80 when Tressell was born? Could it have been Sir Samuel’s son Samuel who was actually the father and the “husband” of Mary Noonan? It seems more likely to have been Sir Samuel, although Kathleen in 1913 referred to him as her “great-grandfather”. [Ball 218] Ball’s attempts to find out more details were inconclusive and question marks remain over the parenthood, the Crokers and the Noonans.

Tressell grew up in Dublin as Robert Noonan (at some point he also acquired the middle name Phillipe or Phillip). He was commonly known as Bob Noonan, although his sisters called him Robert. He was believed to be a “very sensitive and impressionable child” who was “very fond of his father”. [Ball 5] Tressell’s mother Mary was “frivolous, vain and proud of her tiny feet.” [Ball 243]. After Sir Samuel’s death she soon remarried. Robert’s niece said: “Certainly this marriage had a profound effect on Robert, who never, I believe, agreed with it nor took to his stepfather and the stepfather never took kindly to the children.” [Ball 5]

Tressell spent some time in London. But his education was uncompleted, and he seems to have left home in 1886, aged 16, apparently starting an apprenticeship (possibly as a house painter and sign writer) and earning his own living. He never saw his mother again; she died about 1894.

To South Africa

About 1888-90: Tressell left Ireland to start a new life in South Africa, using the name Noonan. This followed his principled decision not to become a student at Trinity College, Dublin, because he did not want to “live on an income from absentee rentals” from property owned by his father. [Ball 243] This was a key point in his life, because his refusal of higher education funded immorally, as he saw it, was to force him to become a manual worker.

By 1890 at the latest Tressell was in Cape Town, the capital of Britain’s Cape Colony, and was probably already working in the painting trade. [Hyslop 67] On 15 October 1891 he married Elizabeth Madeline Hartel, aged 18, at a Protestant church in Cape Town. He was recorded as being a “decorator”. They lived in Rosebank, Mowbray, a middle class suburb.

On 17 September 1892 Tressell’s first and only child, Kathleen, was born in Cape Town. Tressell called her Katie. She was baptised as Kathleen Noonan in Mowbray on 7 April 1895.

Tressell’s marriage was reasonably happy until 1894, but then he discovered that Elizabeth was having affairs, and so in about late 1894 he moved alone to Boer-controlled Johannesburg, in the Transvaal. In mid-September 1895 Elizabeth joined him there, returning to Cape Town that December. In April 1896 he visited her in Cape Town and found she was pregnant, giving birth to a child in August 1896. Tressell subsequently discovered that the baby’s father was a Cape Town cart driver, Thomas Lindenbaum, who had paid her for sex in December 1895. On 27 February 1897 Tressell divorced Elizabeth in Cape Town Supreme Court. She did not contest it, and Tressell was awarded custody of Kathleen, who had been with him in Johannesburg since August 1896. [Hyslop 70-1]

The true fate of Tressell’s marriage was not known to Kathleen and Fred Ball. They believed that Tressell had taken on responsibility for Kathleen following the death of Elizabeth. But then in 2001 Hyslop reported that he had discovered the real story in the records of the Tressell divorce in the Cape Town archives.

Hyslop believes that there are strong and important similarities between Tressell’s marriage failure and The RTP story of Ruth Easton, who is seduced and has a child by the vile Alf Slyme. It had been assumed that the Easton saga was “simply part of the novel’s rich social background, drawing on Noonan’s capacity for invention”. But the divorce record papers make it possible to suggest that the story of Ruth and William Easton is derived from that of Robert and Elizabeth Noonan’s marriage, and that like the rest of the book it is largely autobiographical”. [Hyslop 69-70]

He goes on: “The similarities between Noonan’s court-room account of his marriage, and his fictional account of Ruth and William, suggest that in both instances he was telling the same story.” [Hyslop 71] Hyslop says that Tressell “seems never to have established an extended intimate relationship after his marriage ended” and that he had feelings of guilt towards Elizabeth. [Hyslop 73] “The Ruth narrative may be understood as Robert’s intense attempt to grapple with the experience of his marriage. But he used that engagement to try to think through the relation between personal and social morality. This is a neglected dimension of the [The RTP’s] social and political vision.” [Hyslop 81]

While living in Johannesburg, Tressell worked as signwriter and foreman for Herbert Evans & Co, the town’s largest decorating business. Stewart Ogilvy of Johannesburg worked with Tressell from 1897-9. He told Fred Ball: “He was a very good signwriter indeed, one of the best I have ever known, and he had the makings of a brilliant artist. Noonan was an extremely pleasant fellow and the best of company. … I found Noonan an interesting and entertaining companion. There can be no doubt that he had a brilliant and versatile mind.” His private and domestic life “was not happy”, although he had a good standard of living. He was very attached to Kathleen, who was at a residential school. “He lived in a little world of his own and was very fond of writing, especially articles dealing with everyday life. … Noonan was short and well built. We used to call him ‘little Noonan’. He walked with a sharp energetic step and a slight roll or sway. His speech was good and accent very slightly Irish. He did not mix much with his fellow employees but on the whole he was good little chap.” He spent much of his time compiling a book about Johannesburg, which was shelved because of the Boer War. [Ball 15-7]

But Tressell was also an active trade union organiser and politician before he came to Hastings, as a result of his South African experiences. As Hyslop says: “If Robert Noonan had deliberately set out to select a city where he could examine the worst excesses of capitalism, he surely could not have found one so appropriate for this purpose anywhere on the planet. Johannesburg was already an international byword for greed, commercial swindles and wanton disregard of human life. … Only the difficulty of procuring an adequate supply of labour seemed to moderate the [gold] mine-owners’ attitudes towards their black and white workforce. If The RTP gives us a particularly sharp account of the inexorable logic of the unlimited pursuit of profit, we should remember that Robert Noonan came from a place where that logic worked in a far more unchecked way than in Hastings.” [Hyslop 74]

In 1897, while in Johannesburg, he became secretary of the Transvaal Federated Building Trades Council, in which he played a prominent role. It was also in Johannesburg that he was drawn into socialist politics. In May 1899 he represented the Trades Council at a public meeting which set up an International Independent Labour Party, and he was elected onto its committee. Also on the committee was James Bain, the Transavaal’s first socialist agitator, who may have introduced Tressell to contemporary socialist ideas.

Tressell was also involved in pro-Irish groups, with the Boer cause being a popular one in Ireland. In 1898 he became a member of the executive committee of the Transvaal’98 Commemoration Committee, celebrating the centenary of the large-scale but unsuccessful anti-British rebellion in Ireland in 1798. Also on the committee was John McBride, who was executed in Ireland in 1916 by the British for his part in the Boer War. McBride was one of the founders in September 1899, shortly before the war broke out, of the Irish Brigade, an Irish military unit that would fight with the Boers. Tressell took part in the discussions that led to the creation of the Brigade. [Hyslop 80]

Hyslop believes that “The RTP’s critique of capitalism needs to be seen in relation to Robert’s experience of life in Johannesburg. For someone of Robert’s sensitivities Johannesburg could not but be a lesson in the effects of the untrammelled pursuit of profit. … Johannesburg was the site of Robert’s anti-capitalist revolt, the place where he became a socialist and a labour organiser.” [Hyslop 81]

Hyslop also thinks that Tressell’s experiences in both Britain and South Africa caused a major racism dilemma, as the labour movements in both places supported racial exclusion as legitimate in protecting their existing, white, membership. “In The RTP this moral-political difficulty is dealt with by confining the book’s horizons to a hermetically-sealed white, British world. In a 20th century British labour movement which was to be divided over questions of race and empire, avoidance of these areas of controversy clearly helped to facilitate The RTP’s almost universal popularity. … Leaving his Irish world out of his book also made The RTP more easily palatable in Britain.” [Hyslop 82]

Shortly before the Boer War started on 11 October 1899, Tressell and Kathleen left Johannesburg and moved back to Cape Town. The reasons were probably complex. Although he had been heavily involved in the anti-imperialist movement, he was believed to be opposed to a war. He was also suffering ill-health from what may have been early tuberculosis, and he was the single parent of a young child.

Tressell’s improved financial position as a skilled craftsman meant the couple could live in Cape Town’s securely middle class suburb of Rondesboch, a much more affluent area than Mowbray where he had lived from 1891-94. [Hyslop 84] They shared the house with Tressell’s sister Adelaide Rolleston and her son Arthur, who had come from Chile, via London, following the death of her husband. Tressell had invited them to set up a home with him, and seemed to be earning well enough to help pay for their trip. Arthur died in First World War, and his name is on the war memorial in Alexandra Park in Hastings.

To England - and Hastings

Tressell left South Africa before the Boer War came to an end as a hard-won British victory in May 1902. On 17 September 1901 Tressell, Kathleen, Adelaide and Arthur sailed to England on the Union Castle liner SS Galician. The 6,897 ton, 12 knot Galician had been built by Harland and Wolff in Belfast 1900. She was renamed Glenart Castle in September 1914 and was put to use as a British hospital ship during the First World War. She was torpedoed by a German U-boat on 26 February 1918, killing 162 people, and her wreck still lies underwater ten miles west of Lundy Island.

The SS Galician probably arrived in England in mid-October 1901: After staying briefly in London, the four came to Hastings, probably in late 1901, to join sister Mary Jane Meiklejon (née Noonan) in a flat at 38 Western Road, St Leonards. No 38 stood where today is the water pumping station. Mary had written to Tressell asking him to come to “dear, sunny Hastings”. [Ball 30] There was a partial reunion there with the other sister Ellie, but none of Tressell’s brothers, whom he never saw again. Mary and her daughter ran a school for the blind, the only one of its kind in the town, at 48 Kenilworth Road, St Leonards.

Tressell was still suffering from a bad chest, and in South Africa a doctor may have told him he had tuberculosis. This may be part of the reason for him deciding to stay in Hastings, as it was believed to be a healthy place to live for people with such complaints.

But, as Fred Ball said, “even as a highly skilled workman he couldn’t have come at a worse time for a job. It is true that Hastings had become a ‘superior’ resort, although not so superior as Eastbourne, but with no basic industries, with a higher than average of retired and elderly inhabitants (it still has) and an economy best described as taking in one another’s washing. St Leonards, originally laid out by James Burton, a nineteenth century speculator, had many streets built for the new gentry, many of which in my time became the one- or two-roomed houses for hundreds of lonely remittance women - the spinster relations of the aforesaid gentry, so much thicker than blood is water. But the only industrial buildings were the gas-works retort-houses, built almost in the centre of the town by the cheeky founders, and which belched smoke and the sickly smell of gas over the populace. …

“The town being entirely without factories and industry, the working classes lived off the Corporation (and men literally fought for jobs there), the public utilities, the railways (and horse-buses), shops and hotels (the two worst-paid occupations), and domestic service, or the ‘kiss-me-Aunt’ trades as they were referred to by an irascible elderly working gentleman of my youth who used to carry the hod [Ball’s mother’s father]. And last of all there was the building. “And Robert [Tressell] was dependent upon this, the worst of the lot. The trade was at its lowest ebb for 20 years in Hastings following the developments in Victoria’s reign when most of the town had been built - the population at 65,000 [in 1901] was nearly four times as great as 50 years earlier. But 65,000 was the limit, in fact the numbers actually declined by 5,000 during the eight years Robert lived there.” [Ball 31-2]

In late 1901 or early 1902 the four Noonans moved to 1 Plynlimmon Road, an end-of-terrace house on the West Hill, built in the early 1870s on the site of a windmill complex. The house, which has a Tressell plaque on its front wall, looks down into Priory Valley, and from its upper windows Tressell’s next home, in Milward Road, can be seen.

Tressell acquired a job at Bruce & Co (Rushton in The RTP), electrical and sanitary engineers, builders and hardware sellers. They had shops at 2 York Buildings (now opposite Macdonalds) and 40 Havelock Road (where the University Centre Hastings building is today).There was also a yard and stores near the north-east end of Russell Street (now a private car park). Tressell looked after Bruce’s ironmongers shop in York Buildings and did sign writing. He apparently needed this job because his former good financial position seemed to have gone. With Bruce he was a top-paid interior decorator at 7½d an hour, very skilled, and virtually in a class of his own.

William Gower was an apprentice electrician at Bruce when Tressell started. He remembers working with him at 10 Stockleigh Road, St Leonards, home of Professor WCT Beasley. Tressell grained the front doors. Ball reported that Gower said Tressell “never gave any inkling that he was other than an ordinary member of the working class.” Ball himself then went on: “In fact no one ever raised the question with me that they suspected he might not have come originally from the working class.” [Ball 33] William Ward, a sign writer of St Helens Road, who first came to know Tressell when he was at Bruce’s, described him as: “Fair complexion, with heavy moustache. Think his eyes were blue, but they seemed to have a light behind them. … never seen anything like it in anyone else’s eyes before or since. … He certainly was on the frail side, he suffered with chest trouble, he told me he was often in bed between 10 and 11 and could not get to sleep before 4 o’clock and then had to get up at 6 o’clock for work. … I think a good bit of the book was thought out and written during those hours. … He often said how he liked flowers but could not afford to buy them.” [Ward]

Ball said: “He was about five feet three inches tall and, in his early years here, well knit and compact in build, about nine stone in weight. His hair was of a sandy colour and he sported something of an ‘Old Bill’ moustache, but with ‘military’ points, as I believe our ancestors called this type of decoration. His complexion was ‘fresh’.” [Ball 48] His talks with Gower (and many other people) were very wide-ranging and animated, but on no occasion did he express any hostility to English people because they were English, and The RTP is entirely free from nationalism.

Tressell was described by other people as being short, with a slight Irish accent, atheist, very cultured, reader of a wide variety of books, an alcohol consumer, kind to his friends and fond of cricket. He could speak at least seven languages. “In the week he was dressed like his mates, except that he always wore his trilby hat to work, never the cap common to most working men. He always wore a painter’s apron, and made little effort to keep it clean, but he didn’t sport the painter’s white jacket. On Sundays, he dressed smartly, almost dapperly, usually in a grey ‘fashionable’ suit, soft hat or ‘stetson’ set at a tilt, and he liked to carry a walking stick.” [Ball, 1951, 40-1]

He was “a man who wore his heart on his sleeve, where it ought to be, and … he had a completely open and natural manner with people.” [Ball 34] But “openness of character is the last thing required in our society, especially in business and official relations. … I believe [he] had had no direct experience of English class society and working conditions and could not know that … for a man even to look intelligent is considered an affront.” [Ball 35]

The first school for Tressell’s daughter Kathleen was the Aylsham House School, a terraced house at 21 Vicarage Road, just round the corner at the other end of Plynlimmon Road where they were living. Next she went to the Roman Catholic school at the Convent of the Sacred Heart, in Old London Road. After that, some time late in 1902, she was sent to a fee-paying Catholic convent school in Deal. During 1904 she moved to the free St Andrews Church of England (ie, Protestant) Elementary School in Stonefield Road, Hastings, presumably because money was short. In 1908 (possibly 1907) she received a bursary to St Helens Pupil Teacher Centre, later St Helens High School for Girls.

Milward Road

By late 1902 the four Noonans had again moved, this time to the top flat, number 5, in ‘Grosvenor Mansion’, 115 Milward Road, where there is now a marble plaque. The building was not a mansion, just five flats, with Tressell’s perched awkwardly on top. “The flat, an architectural curiosity of three attics, allowed for a small room for Robert, a separate bedroom for Kathleen and a room for mother and son, plus a communal sitting-room, but no bathroom of course in those days.” [Ball 43]

Tressell had many books, but not much furniture. The house was below 1 Plynlimmon Road, and had the view of the railway he describes on page 586 of The RTP. Ball believed he stayed there until 1906 [Ball 49], although the plaque says he was there from 1903-5. The contemporary Pike’s street directories have him there in the 1903-6 editions, which means from the autumn of 1902 to at least the autumn of 1905, but he is not at any address in any edition from 1907 onwards. No 115 was at the top of a flight of steps, at the bottom of which was St Andrews School.

While living at 115 Tressell built a model airship. He had been very interested in flying, then in its birth phase, since at least arriving in Hastings. He wrote an article The Evolution of the Airship and illustrated it with his own drawings, possibly in 1901-2. It was never published, but it is the only other writing by him which survived. He built the six feet long model in 1905-6.

“With the boy, Arthur, he [Tressell] was on terms almost of father and son and many of the incidents about children in the book are based upon these two children. … The boy would watch for Robert to come up the road from work or up the long steps running down past the flat to Stonefield Road and when Robert arrived would run out and throw his arms round his uncle’s neck regaling him with tales of the day’s events. Gower says that Robert used to go into the children’s rooms and stand awhile looking down at them. He often spoke bitterly and sadly of the fate of drudgery and want which so many children had to endure and of the future blunting of their fine perceptions, of the loss of the happiness and gaiety natural to childhood. The relationship between himself and the children is delightfully brought out in the book in different ways through the various child characters. But between brother and sister [Tressell and Adelaide] it appears the atmosphere was neither as free and easy nor as cordial. They weren’t apparently on very brotherly and sisterly terms.” [Ball 46-7]

Adelaide disapproved of his ideas, and she rebuked him for attacking religion in front of the children. He was much more of a father to Arthur than Adelaide was a mother to Kathleen. In 1906, when they left Milward Road, Arthur would be about nine years old. [Ball 49]

In late 1902 or early 1903 Tressell left Bruce & Co because he was fed up. He particularly disliked the foreman, whom he combined with the foreman at his future employer Adams & Jarrett to form The RTP’s nasty chief foreman Nimrod/Misery/Hunter. Working on the roof of the Post Office in Kings Road he told his mates he would kill the foreman if he came up Tressell’s ladder (but he did not).

Ball thought that after Tressell left Bruce & Co he spent up to six months seeking work in London, but failed and had to come back to Hastings. The Painter’s Journal in 1922 said that that period was immediately after arriving from South Africa, but Ball believed not. [Ball 40-2] “I’ve no doubt that Robert himself had real experience of London, and this, together with Bruce’s cured him of any illusions about work in England and the status of the workman, whether craftsman, artist or labourer. And it wasn’t his temperament alone which made him detest the set-up and the lack of a real human relationship between employers and men.”

Ball said Tressell’s new working life in Britain had an “obviously profound effect” on him, “making him put work and conditions of its performance at the centre of his book. It is from the shock of his experiences with Bruce & Co that I date the real origin of the passionate sense of outrage which was to inspire and light up The RTP; and, perhaps, the beginning of the deep sense of loss which he was to feel over the rest of his short life.” [Ball 42] Tressell may have spent some of his weeks in London in hospital, although this is not certain.

“Employers in those days took it for granted that our forerunners were long-distance walkers and nocturnal in their habits. Any job within about a ten-mile radius had to be reached on foot - and six o'clock was the time on the job. Men sometimes had to start from home at three and four o'clock in the morning and pad it, rain, snow, thunder or lightning, often arriving saturated, to work in empty houses or on building sites without fires for warmth or cooking. Luckily, builders don't feel the wet and cold as other people do. The secret is that they varnish the naked skin before dressing. In summer you might be on a job for thirteen or fourteen hours, when you were then at liberty to walk home, and if your wife was still up and hadn't locked you out, she would serve a meal for you. Work was broken for short periods of sleep during the night, no method having been discovered of working men for the twenty-four hours and keeping them alive. Just the kind of life for a man with a weak chest. Men who worked with Robert tell me of such journeys to villages like Ninfield, Mountfield, Crowhurst and Netherfield, all many miles outside Mugsborough.

“And if the job was too far, even as employers calculated mileage, then the men would pack a week's food in the time-honoured wicker-basket and live on the job, sleeping at night on the floors amid the dust and the paint-pots, the plaster and the shavings. One can picture the old building-workers tramping through the dark overhung Sussex lanes, dressed in their drainpipe trousers, caps and bowlers, and a rare collection of second-hand clothes, the rain dripping off their walrus moustaches. One can sympathize with their imprecations on work and the weather and the size of the country, and the slowness of time.

“Many men who couldn't get work in Hastings managed it in better-off Bexhill, where the rate, by one of those strange quirks, was a penny an hour higher, and walked there by six o'clock in the morning and left for home at half past five in the evening — unless there was overtime! And Bexhill was only four and a half miles. …Semi-starvation, exposure, and the blunting of the mind by such a life were the greatest enemies of the very poor.” [Ball 56-7]

After leaving Bruce & Co, Tressell worked for Burton & Co, an undertakers and general painting and decorating business. It had a shop at 88 Stonefield Road (on the south corner of Stonefield Place, opposite the bottom of the steps coming down from 115 Milward Road), where the firm remained until the 1980s. Today it is a plumbing shop. There was also a workshop on the other side of Queens Road, at 2 Waterworks Road, now demolished.

The company was run by Herbert Burton, who Ball described as a typical The RTP character, being both a pillar of the local church and a tough and mean employer. Burton thought Tressell was “difficult” but kept him on because he was more than worth his money. [Ball 52] Tressell spent most of his time with Burton on general work, but, being a signwriter, he also wrote coffin plates, as he did with all the firms he worked for. Ball saw Burton’s ledger, which recorded in 1905: “Dec 25th. R Noonan, writing coffin plate, one hour.” [Ball 54] Ball said on page 58 that Tressell worked for Burton for “about four years” which would mean until late 1906 or early 1907, although on page 88 said he quit Burton in 1906. He then went to Adams & Jarrett in Norman Road, St Leonards.

Ball thought that many of The RTP incidents seem to be based on Tressell’s experiences at Bruce and Burton’s, and that much of the atmosphere of the book comes from Hastings rather than St Leonards, even though he probably wrote most of it in St Leonards. [Ball 58] At this time Tressell is known to have worked at: Kite’s Nest, a detached house on St Helens Park Road, by Hillside Road; [Ball 96] and the Imperial pub, on a corner of Queens Road, next door to Burton’s shop. [Ball 97]

Another job for Burton was Tressell’s high quality artistic renovation of the chancery of St Andrews Church in Queens Road. The church was built in 1869-70 and stood where the Morrisons petrol station is today. Herbert Burton redecorated the chancel as a gift to the church, and it was completed by Easter 1905. In 1970 the church was demolished, but a small part of a 20x40 ft mural painted by Tressell was rescued and is now on display in Hastings Museum (see below). This is the only surviving example of what is known for certain to be Tressell’s work.

A rare official glimpse of Tressell came at Hastings magistrates court in November 1905. A “Mr Noonan, a decorator, of 115 Milward Road”, was fined ten shillings and £1 9s costs for obstructing a police officer who had “cautioned a lad for lighting a squib in Havelock Road” on 6 November. Tressell said the constable, in plain clothes, had violently seized the boy and Tressell was only defending him. The law prevented fireworks being let off in the street, although Tressell did not know this. [Observer, 11 November 1905]

The Cave

Ball said that from September 1903 to June 1904 Tressell and most of Burton’s staff worked at Val Mascal, a large house in Hollington Park Road. It was here that Tressell “is said to have decorated the Moorish room and some have told me that this was the famous ‘Cave’, the setting for the book.” [Ball 58-9]

The real-life identity of the Cave has been the subject of much debate and speculation. The most likely answer is that it was modelled on a number of houses, with Val Mascal being the main one.

Vale Mascel, as it was called before the First World War, was one of the biggest houses on the Hollington Park estate. The estate had been created in the 1870s for the wealthiest people in Hastings and St Leonards, and the houses were all well-designed detached properties surrounded by large gardens. Ball seemed to believe that Vale Mascel was owned by “a boot-manufacturer, Upson, a prominent figure in the town”. [Ball 58] But this was partly incorrect.

The house was built about 1891 for Mr John H Upson, who occupied it until he died in about 1910, when his family continued living there until 1936. All the street directories of the 1890s and 1900s only record Upson in their ‘Court Directory’, showing he had a private income. Upson never figures in newspaper stories, and there is record of him being involved in any local businesses, politics, religion or social work, so he does not seem to have been a ‘prominent figure’. Listed separately in the directories is Mr W Upton, a ‘boot manufacturer’ with a large town centre shop at 1 York Gardens, next to Bruce and Co. Upton would have been well-known by name, if nothing else, so it seems that Ball mistook Upson for Upton.

Upson also owned another large house in Hollington Park, West Dene, which is known to have been a place where Tressell worked. In March 1906 Hastings Council gave Upson planning permission to build an “entrance lodge cottage” for West Dene at its back entrance in Avondale, and in May 1907 to carry out “alterations and additions” to West Dene itself. [HBC minutes]. West Dene was almost certainly part of the ‘Cave’. Len Green worked there with Tressell, and recalled how the workers would have ‘meetings’ at dinner-time, to pass the time away. Tressell would talk, and the others would listen, and sometimes jeer at him. [Harker 37]

Also probably included in the ‘Cave’ was Filsham Lodge at the top of Filsham Road. This was built about 1890 and was one of the first residential properties in what was called Filsham Park from 1895 until 1927. The Lodge was built for a physician, Mr Adam Bealey, who in 1905 sold it to Henry B Philpot, the well-known St Leonards businessman who ran a leading drapery shop, in the colonnade at 37-8 Marina. This family-owned business had been in those premises since 1836, and it was to remain there for 150 years, until closing in 1986 because of the degeneration of St Leonards.

In August 1905 Philpot was given planning permission for a “new porch to entrance and motor house, etc” at the Lodge. [HBC minutes] In The RTP, the workers in the Cave are having a meal break “and a desultory conversation ensued. ‘Is the gent what’s bought this ‘ouse any relation to Sweater the draper?’ asked Payne, the carpenter’s foreman. ‘It’s the same bloke,’ replied Crass.” [The RTP 19] This, and the book’s description of some features in the building which are synonymous with Filsham Lodge, could be interpreted to mean the ‘Cave’ is Filsham Lodge, and ‘Sweater’ is Philpot. But the workers go on to say how Sweater was then the mayor, and had been several times before, whereas Philpot was never mayor. [The RTP 20] They also discuss how the house’s cesspit was to be replaced by a new drain going out into the road. There is no mention of this in the planning permission for the Lodge, but there is in the March 1906 permission for West Dene lodge, with Hastings Council saying that instead of a cesspit, the lodge should connect to the main sewer in Hollington Park Road.

So the ‘Cave’ seems to be an amalgam of at least three Hollington Park houses where Tressell apparently worked: Filsham Lodge, West Dene (and its lodge) and, most prominently, Vale Mascel (now Val Mascal). Experiences elsewhere in the town also probably coloured Tressell’s picture of the ‘Cave’.

Politics to 1907

In the municipal elections in November 1904 the Liberals took control of Hastings Council from the Tories. The Liberal Hastings Mail said it was a “sweeping condemnation of Tory municipal policy … Hastings is disgusted with municipal mismanagement, muddling to extravagance. … For a long number of years our Corporation has been ruled by expensive Tory partisans.” [Mail, 5 November 1904]

But the Tories hit back hard in the general election on 15 January 1906, taking the Hastings seat from the Liberals. This played a major role in creating an active socialist and labour movement in Edwardian Hastings, and probably in prompting Tressell to write his book. It was the first general election since Tressell arrived in England, and was “fought against the background of a declining standard of living for the working classes, but not for the rich. Purchasing power in 1905-6 was well below that of 1900, but profits were soaring. Taxation was mostly indirect and on articles of common consumption so that, as now, the heaviest fell on the ordinary people.” [Ball 71]

The Hastings Liberal MP Freeman Freeman-Thomas was expecting to retain his seat, but he lost to William Harvey Du Cros, the rich Dublin-born founder of the Dunlop tyre business. It was a shock result, with Hastings one of only a handful of towns across the country being taken by Tories from Liberals, when the election overall was a major victory for the Liberals. The exceptional Hastings result sparked comment around the country. The Hastings Mail said: “Our feeling is summed up in one word - disgust, disgust at the ludicrous position in which our town is placed in view of the overwhelming opinion of the country against Mr Balfour. … Hastings Tories fought a political fight in 1900 and were worsted; they knew that their only chance to retrieve that disaster was to introduce a millionaire. He came, and aided by powerful combinations, strange artifice, peculiar methods, his capital triumphed.” [Mail, 20 January 1906]

Just before the election the Hastings Mail had warned that the Conservative Party had “over and over again done their very best to wipe their feet on the working man. … Mr Du Cros and his friends are past-masters at the game of bluff.” [Mail, 13 January 1906] After the election, on Sunday 21st January, in the big Public Hall in Robertson Street, the Rev John Bailey gave a public service, condemning the people of Hastings for supporting “ancient fossiliated and encrusted Toryism … in this age of progress and liberty. I thought, in my simplicity, that the day was gone, even in Hastings, for the descendants of heroes and martyrs to allow themselves to be bought and sold like dumb driven cattle. I would not believe that men could be so idiotic or ignorant as to be led astray by false promises or delusive hopes. I was mistaken. I knew there were some fools in Hastings, but I was unaware that they were so numerous. … Poor, deluded, benighted, infatuated and demented Hastings.” [Mail, 27 January 1906] These were views Tressell seemed to share in his novel.

The Du Cros victory shocked the anti-Tory political activists of Hastings. How could they fight back against the wealthy Irish tyre-maker? A few days after the election Frank Willard, a shopkeeper at 224 Old London Road in impoverished Ore, initiated the setting up of a Hastings branch of the National Democratic League (NDL). The NDL had blossomed briefly after the 1900 general election in the doomed hope of uniting Radical Liberals, Labourites and socialists into one large democratic body for the common good. [Matthews 15] But it was primarily Liberal, and had therefore been made largely unnecessary by the Liberal victory in the 1906 election.

The NDL at a national level also faced a rival pro-working class group: the Labour Representation Committee (LRC). This had been set up in 1900, as had the NDL, by a conference of trade unionists and left-wing organisations aiming to co-ordinate attempts to support MPs sponsored by trade unions and to represent the working class. A Hastings branch was formed. The LRC had won 29 seats in the 1906 election, and on 15 February that year these MPs adopted the name ‘The Labour Party’. The party did not have individual membership until 1918, however, so the Independent Labour Party (ILP), set up in 1893, immediately affiliated to the new Labour Party and provided much of its activist base. But in Hastings the local LRC, set up in 1904 or earlier [Hopper 25], remained in existence until 1907.

Both the NDL and LRC had been made almost redundant by the 1906 election, yet both were to be at work in Hastings over the following months. A large meeting of people, many of them known Labourites, took place in Ore on Wednesday, February 7, and founded a Hastings NDL branch, with Willard elected as secretary. Why was a branch of the withering NDL actually created in Hastings after the election, when a local LRC group already existed? Presumably, the Hastings LRC had been ineffective and the worried local activists felt the NDL was their best hope. The Hastings Mail commented: “The movement for the organisation of the democratic forces of Hastings and St Leonards has made a decided advance this week.” [Mail, 10 February 1906] The Hastings NDL’s 12-strong committee included a Frederick Owen, upon whom Tressell was to partly model Frank Owen, the leading character in The RTP. Fred Owen then lived at 18 Edgar Road, Clive Vale, about 100 yards from where Tressell’s biographer Fred Ball was to live three decades later.

The only other organised ‘political’ force in the town in early 1906 was the 800-strong Hastings Trades and Labour Council (TLC), which had been set up in 1894. On 10 May 1906 the NDL and TLC held a meeting in the Lower Central Hall in Bank Buildings in the town centre, where it was agreed they would form an alliance in the November municipal elections. A week later delegates from both groups met to draw up an action plan.

But during the summer months of 1906 the NDL began falling apart. Its committee developed its own socialist identity that was out of step with both its mainly Liberal membership and with the more moderate union-oriented TLC. The committee held public meetings on the seafront every Sunday through the summer, with most speakers being active socialists, often from the Socialist Democratic Federation.

Author Mike Matthews recalls: “As a movement of national importance, the SDF had a stormy history. Originally associated with the Radical workingmen’s clubs, it was founded by Harry Hyndman in 1881 under the name ‘Democratic Federation’ and only adopted its full title in 1884 as its programme shifted towards a revolutionary brand of Marxist socialism. Its wide-ranging political programme attracted many diverse left-wing groups into its fold - anarchists, socialists and social revolutionaries - elements that caused bitter internal wrangling, and gave the organisation a turbulent and chequered career. Remembered today as Britain’s first socialist political party, the SDF survived an endless succession of splits and traumas to eventually merge with the Communist Party in 1920.” [Matthews 18]

Over the summer of 1906, working class politics in Hastings polarised. In September the pro-SDF movement had become so strong that a local branch of it was set up following a meeting held in the Cricketers pub in South Terrace. Among those present were Tressell, Alf Cobb and Edward Cruttenden.

Alf Cobb (1874-1921) was a greengrocer and street hawker from Hackney. He was an impassioned socialist who devoted much of his life to publicly and forcefully campaigning for better lives for working people. He soon became the leader and figurehead of the Hastings SDF and would have been some form of friend of Tressell. His full biography is in Alf Cobb: Mugsborough Rebel, by Mike Matthews. Edward Cruttenden, of 16 Wellington Square, was the founder of the Hastings Trades and Labour Council in 1894. He had also tried to set up a branch of the SDF in the 1890s, but it did not last long.

On the evening of Friday 12 October 1906 the new SDF had its first open meeting, to officially launch the branch, in the Beehive Dining Rooms, 32 Pelham Street (where the rear of the former Woolworths is today). The chairman at that meeting was Fred Owen (the chairman was to be appointed from meeting to meeting) and JM Kerr was elected as permanent secretary. Its members included many members of the committee of the NDL, whose leading personality Willard told an NDL meeting on September 9 that he no longer supported it, and was sympathetic to the setting up of an SDF branch.

Tressell probably played a role in stimulating both the increased level of public political debate and activity in Hastings that followed the 1906 election, and also the rise of the SDF. His South African experiences in politics and trade unionism would have given him a wider and deeper understanding of the need for a radical movement than that of most Hastings political newcomers.

Ball believes this radicalisation of Hastings inspired Tressell, and that it throws light on The RTP. Tressell was a convinced socialist, being part of his nature. But until 1906 he was in some isolation in Hastings. “Only when the socialists finally began to organise independently did he find the organisation and comradeship to meet his need, and it seems to me no accident that this should have been the impulse needed to call out his particular kind of talent and give it direction”. [Ball 81].

The NDL slipped further off the local stage on 25 October 1906 when the TLC dissolved its connection, saying it would field its own candidates in the local election. Then on 8 November the LRC received the same treatment, with TLC delegates withdrawing from it. By the end of 1906 the NDL and LRC had both shrunk in size and had been effectively taken over by SDF members and their supporters. The aim of the SDF (and, de facto the NDL and LRC) was to overthrow capitalism, while the trade union-backed TLC believed that capitalism could be reformed and that workers’ conditions could be improved within a better system, a view shared by Liberals.

Mixed up in these debates were strong personality clashes which shaped much of Hastings’ political life. Frank Willard and Alf Cobb had especially forceful rows, being strongly opposed to each other, despite sharing similar political views. In the early days of the SDF there was a power clash between them, with Willard claiming to be secretary, when he was not. A split then developed in the SDF, with public feuding and rivalry between the old leadership of the NDL - secretary Willard and chairman John Thompson - and the resolute upstart Alf Cobb. [Matthews 21]. Willard eventually lost. He and some of his supporters then quit the SDF and LRC, leaving them in the hands of Cobb and his comrades. By late 1906 there were socialist and Labour groups all over the town, with the SDF the most active. “I believe this local situation played a part in determining how Robert [Tressell] was to portray the role of socialism and socialists in the book”. [Ball 87].

But this did not bring any anti-Tory success in the municipal by-elections held in four wards on 26 November 1906. The Tories won all the seats, including Silverhill/Hollington, where plumber Walter Jones stood for ‘Labour’, the first time there had been any ‘Labour’ candidate in a municipal election. But was he a real ‘Labour’ candidate? He stood for the TLC, but was disowned by the LRC (almost the SDF by another name) because of his lack of socialist beliefs and his backing by the Liberals. The Hastings Mail said it was clear that over the past few months a big split had developed between the Trades Council (just focusing on trade unionists) and the SDF, which had few trade unionists as members. [Mail, 17 November 1906]

The SDF dominated the Hastings political scene throughout 1907, holding many meetings and obtaining much newspaper coverage. The Hastings Mail was Liberal-owned and oriented, and reported the political upheaval of 1906 in detail, but by the end of the year had lost much of its sympathy for Cobb and the SDF. The Tory-owned Hastings Observer was always hostile to the non-Tory movements and would have given them minimal coverage, but was forced to run stories in combat with the Mail. Together the Mail and Observer ran a large quantity of news that was a valuable source of material for Tressell while writing.

It was the extensive coverage of the SDF, and Cobb’s ongoing publicity as a dynamic socialist leader, that probably prompted Willard and his backers into playing a leading role in setting up a Hastings branch of the Independent Labour Party. This took place on Tuesday 16 April 1907 at a meeting of 25 people in the Ferrari Brothers café at 28 Havelock Road (now part of the John Logie Baird pub). The chairman was Walter Campling, who said he had “not yet found it desirable to attach himself to either of the orthodox political parties - Liberals and Conservatives - which were equal in that they ‘did next to nothing for the working classes’.” He had decided to attach himself to the ILP, whose object was “to establish an industrial commonwealth founded upon the socialisation of land and capital”. Speaking of the condition of the working class in Hastings, Campling said there were many who earned only £1 a week, and half of it was claimed by the landlord. [Mail, 20 April 1907] There were several SDF members present, including Alf Cobb and secretary JM Kerr, plus Fred Owen and Edward Cruttenden. [Observer, 20 April 1907]

The Mail of 20 April went on to say that within twelve months three parties had been formed in Hastings: “First we had the National Democratic Federation, which began well but ended feebly; then there was and, we suppose, remains, the Social Democratic Federation, the creation of a company of young enthusiasts who found the milk of the [National] Democratic Federation somewhat watery. The SDF has certainly never been lacking in presumption, for countless communications from that august body have appeared on the agenda of the Town Council. But the latest recruits to the ranks of labour or socialist organisations breathed existence for the first time on Tuesday evening, in the shape of a branch of the ILP, and which most of us understand has been created because the SDF milk was too strong for the liking of some of the social ‘upheavers’.” The Mail editorial comment saw Campling as mesmerised by the presence of Cobb and Kerr.

Despite widespread Labour/socialist activity throughout 1907, the municipal election held that November was fruitless. Two Labour candidates stood: William Jones again, this time in St Clements, and Walter Campling in Upper St Marys, but both were unsuccessful. And two Liberal councillors lost their seats to the Tories.

Tressell probably decided to write The RTP as he witnessed during 1906 and ’07 the rise in poverty and despair in Hastings, and the dramatic but ineffectual fightback by socialist and Labour campaigners - while the Tories and bosses increased their voting box support from The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists.

As Ball said: “One of the main themes of The RTP is the demoralisation of people by the ‘Capitalist System’, employers and men and womenfolk alike … fear of unemployment could demoralise men …Among the results of these conditions were fear, apathy, often poor workmanship, backbiting, tale-telling, crawling and petty fiddling. The bosses themselves set the example. Robert hated the spectacle of men fighting among themselves like this instead of organising to fight for better pay and conditions.” [Ball 119-20]

“There was a serious recess in the trade and many small firms were in desperate straits and could not face the fierce competition. The more conscientious they were the more difficult was survival. As Robert says, the competition demoralised employers as well as men. The employers were mainly small or smallish firms engaged in cut-throat competition among themselves and at the same time at the mercy of the big manufacturers of materials. The slump in building, the introduction of ‘labour-saving’ methods, the skimping and decline in standards produced by the competition, the increased production of inferior mass-produced materials, all of which are savagely or humorously criticised in the book, led to increased insecurity which meant greater risk of unemployment.” [Ball 121]

In the non-industrial South Coast, trade unions were weak and “could not appear to the men to offer a solution in places like Hastings. Hence the insistence of socialists in those days upon a fundamental change, and to a man like Robert it would appear that he must use his energies to fight for what must have seemed the only real and lasting remedy.” [Ball 121-2]

During 1907 Tressell threw himself into SDF work. Unemployment had reached its highest level for 20 years, and tough action against socialists by police and employers meant the SDF branch developed a hard core of militant socialists, among them Tressell. It met regularly in the Beehive in Pelham Street, and that summer, the SDF “were a leading light among ‘The Reds of the South-East’” [Harker 33], with many events taking place. Hastings SDF acquired its own van, which they fitted with a screen on the back and a magic lantern for slides inside. It was very entertaining and popular, and the lantern was also used at meetings at 11 Priory Street. The RTP scene called The Pandorama (chapter 29) is clearly based on this lantern. Tressell wrote numerous leaflets, manifestoes and election addresses. He also took part in many processions, carried collecting boxes and painted banners for the unemployed.

One banner survived until 1940 and is in a photo, but its fate since 1940 is unknown. Another photo shows Tressell and daughter Kathleen at a beach meeting being addressed by Harry Quelch, probably in June 1907.

Tressell’s experience in South Africa probably encouraged him to take part in the SDF campaigning as much as possible, but he was limited in what he could do because he was a single parent, suffering increasingly from TB, with an income becoming more uncertain, and little, if any, family help.

The St Leonards Move

At some point in 1906 Tressell quitted working at Burton’s, possibly because of the conflict and trouble he experienced there, and went to Adams & Jarrett in central St Leonards. [Ball 88] Adams & Jarrett - Makehaste and Sloggem in the novel - was a building and decorating company that had started in 1905. Alfred Adams, a general builder, until then had been running both a gas-fitting business at 22 Gensing Road with a workshop at 44 North Street, and a plumbing and decorating business at 20 Alfred Street. The three premises were within about 200 yards of each other, with 20 Alfred Street at the top of a flight of steps from London Road. In 1905 he and a Mr Boaz Jarrett of Silverhill set up Adams & Jarrett, basing it at 20 Alfred Street.

Early in 1906 they rebuilt the shopfront there. It is known that at some time Tressell painted an Adams & Jarrett advertisement on the London Road side of that building, and he may have done this during the 1906 rebuild. Much of this wall was later demolished, but a section with some of the sign on it was left standing. Until 2006 the words “Adams & Jarrett” were visible, the last-known survival of Tressell’s work still in its original location. But during that year it was painted over.

When working for Adams & Jarrett, Tressell is known to have painted a large company advertisement on the end wall of the last house in Perth Road, Silverhill, on its corner with Battle Road. Jarrett had lived for some years at 50 Battle Road, the house immediately adjoining the Perth Road property. This advertisement was visible until the mid-1960s, when it was painted over after the firm changed hands.

In 1908 Adams & Jarrett moved out of Alfred Street to 12-14 Norman Road, advertising themselves general builders and decorators. By then Adams had given up his Gensing Road and North Street businesses. Nos 12-14 are part of today’s large retail electrical premises still using the name of ‘Adams & Jarrett’.

While working for Adams & Jarrett Tressell was paid 7d an hour, and the usual work hours were 6am to 5.30pm, with no holidays or bank holidays. They were the last builders that Tressell is known to have worked for before leaving the town in 1910. Ball said “Much of the material in the book is based on Robert’s experience with this firm.” [Ball 115] But this conflicts with earlier statements by Ball that it was his work with Bruce and Burton that shaped his view of life. Ball also said on page 99 that “I believe he decorated about this time [when working for Adams & Jarrett] the Moorish room, mentioned in the book”, but on pp 58-9 he said he did that work in 1903-4 while working for Burton. This apparent contradiction by Ball should not, however, detract from the high respect that readers should have for his work. It seems that Tressell worked in many parts of Hastings and St Leonards, irrespective of who is employer was, and this created the overall view of the town.

Other work that Tressell is believed to have carried out in St Leonards (but not necessarily for A&J) was at the Buchanan Hospital in London Road (a scenic wall); the Post Office in Kings Road; the Presbyterian Church of St Columbia, probably on the north-west corner of Warrior Square, destroyed in the Second World War; St Johns Church, Hollington (this is uncertain); and a door in 10 Stockleigh Road. In Hastings, for Burton he is known to have painted part of St Andrews Church in Queens Road, and is believed to have worked on the Imperial pub, Queens Road, adjoining Burton’s shop in Stonefield Road. In addition, for Bruce or Burton he probably worked on Kite’s Nest, a large detached house on St Helens Park Road, by Hillside Road, owned by Lt Col Waddell, and he may have worked on Christ Church, Ore (this is uncertain).

Also during 1906 the four Noonans moved out of the flat at 115 Milward Road, going to unknown addresses at Warrior Square and St Johns Road. [Ball 89] Then in late 1907 or early 1908 Tressell and Kathleen moved into a flat at 241 London Road, St Leonards, without Adelaide and Robert. Tressell and Adelaide were not believed to feel ‘brotherly and sisterly’ towards each other, a feeling he had with all his sisters or brothers, each of whom seemed to dislike his radicalism. Kathleen said: “Adelaide like the rest of the family did not approve of Robert’s social ‘descent’ and possibly she came to the end of her tether and may have returned to the family. I don’t remember them after Warrior Square except for seeing Arthur walking in crocodile with the choir boys on the way to the Church – all the boys in Eton suits and mortar-boards. … Arthur called Dad ‘Uncle Robert’. I think Arthur looked upon him as a father and that would be the relationship between them.” [Ball 102]

It was in this flat that Tressell wrote most, if not all, The RTP. The flat (not self-contained) was at the top of 241, on the fourth floor over a cycle shop, the Adna Cycle Depot, owned and run by Charles Alfred Beney. Kathleen said: “On the top floor was a big front room which was Dad’s and where he did his writing.” [Ball 103] From the back room of the flat he could see the Prince of Wales pub in nearby Bohemia Road, which in the 1990s was bequeathed to the Hastings Labour Party and is now the party’s local headquarters.

1908 Onwards

By 1908 a serious recession had hit the national building trade. Many small firms were in dire straits, bringing cuts in standards, plus insecurity and greater risk of unemployment and seasonal lay-off, all of which is recorded in The RTP. With scarce jobs and weak trade unionism in South Coast regions, the unions did not offer workmen a solution in places like Hastings, where unemployment was a serious problem.

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was also proving a disappointment to radicals. In March 1908 there was a Parliamentary by-election at Hastings, with no ILP candidate. In a snap election, Harvey Du Cros MP announced on 23 February that he was standing down because of poor health, and the election took place just 13 days later, on 7 March. There was no Labour or socialist candidate, and the Liberal vote was poor, with the Tory majority increasing from 413 in 1906 to 1,108, on a total vote of 7,972. The new MP was Harvey Du Cros’s son Arthur, chairman of Dunlop Rubber. He was to retain his seat at the next general election, on 15 January 1910, when again the only other candidate was a Liberal. Du Cros’s majority in 1910 was down somewhat, being 801 on a total vote of 8,467.

Nationally, in 1908 dissident ILP branches joined the SDF, and near the end of the year it changed its name to the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Alf Cobb became secretary in 1908 “and the branch became a real force”. [Ball 123] He brought into the arena a touch of glee and irreverence for the bigwigs. The SDP conducted street meetings in many parts of the town and put up candidates in local ward elections. “Some of the jiggery-pokery uncovered by Cobb went into Robert’s book and I’m sure Cobb’s uncompromising, sardonic and fearless style helped to fire Robert [Tressell] to speak his mind.” [Ball 123]

It is not known how politically active Tressell was in 1908. A photo taken at a ‘Right to Live’ unemployment rally in Wellington Square on 10 October 1908, the same day as a national rally in Trafalgar Square, shows a man looking very much like Tressell addressing the crowd. One of the best-known photos of Tressell, where he is sitting on a gate, was probably taken in Old Roar Gill in the summer of 1908.

At that time Tressell was still living alone with Kathleen. Ball said: “Why didn’t this lonely man ever remarry? In fact none of his friends ever remember him having any women friends, the company of women, or any hint of sexual relationship. Kathleen says that he may not have felt the necessity for a woman’s company, that he worked hard and was not very fit. His book treats sex in a rather romantically honourable way but nevertheless with sympathy and understanding of the married state as ‘natural’. It is possible that being the man he was and believing that he was tubercular he may have determined not to remarry or even to run the risk of infecting a woman friend. On the other hand he may have had other scruples or simply, in his circumstances, lack of much opportunity and no desire for promiscuity.” [Ball 132-3]

“There is no doubt that having a motherless daughter had a profound influence upon Robert’s outlook. He was in an extremely vulnerable situation and he knew it and must have been filled with fear of the future, a fear which forms one of the themes of the book.” [Ball 135]

Ball believed that “In his workmates he saw men like himself for whom there was no escape. Yet they had a way of coming to terms with their situation without becoming wholly contaminated. And they had a strange ability not to become so dispirited as they ought. This gave him a deeper understanding of the working classes, opened his eyes to their deep roots and their resilience which he almost unconsciously portrays all through the book, even when most exasperated about them, indeed perhaps in that very exasperation itself. And gradually his own circumstances made him realize that he had little more chance of ‘escape’ than they had and this gave him a feeling of total involvement. He was hardly any longer a man outside looking in although this feeling he never completely overcame because this is not a matter of will but of nurture. He was not quite of them but was wholly with them. “He found only partial fulfilment in his work for the SDP branch, although this was vital to him in many ways, but his were not the talents of the public leader and organizer such as Cobb, and he could not fully express himself or work to his capacity simply as a party member. He had to do more.” [Ball 137]

In 1908 he was not robust but did not look too sick, although he suffered from coughing. However, this became steadily worse in 1909. “By 1909 his friends and workmates were beginning to notice a marked decline. In the winter of 1909-10 he was having serious attacks and spending more time at home than at work, though in better weather his health would improve.” [Ball 150] He was described by his workmate Cradduck: “Bob was very thin and looked a sick man. He used to come to work for about two days and then he would be away for two or three weeks. He always looked cold and pinched - looked as if he needed a good meal.” Kathleen said “he would have recurrent attacks of bronchitis and would cough and cough.” [Ball 150]

The Manuscript

The writing of the final manuscript of The RTP probably took place between late 1908 and early 1910 as Tressell became more ill and could therefore probably not do many other things. “It is difficult to get a clear picture of how he lived during these last years, especially in 1910.” He did some odd-jobs, as he had letter-heads printed saying “Signwriter and Decorator, Blueprinting” [Ball 151]. He may also have pawned or sold some possessions. He did not seem to have any reserves.

It is not known exactly when Tressell started writing the book, or when he finished its draft, if there was one in a strict sense. He was often writing when living at Milward Road from 1902-6. This may have been the manuscript or advance notes, or something else. Ball thought Tressell had “projected a book” (The RTP) in 1903-4 or even earlier, and began organising and writing it in 1907 from notes written earlier. [Ball 140] Internal references in The RTP correspond to known events from 1906-9. Ball thinks he probably finished a main draft in 1909, and then spent many months making a fair copy, which he may still have been working on in April 1910. He must have finished around that time, because he then began planning to move to Canada.

Tressell may have thought that the title should be “The Ragged Arsed Philanthropists”, ragged arsed being an old colloquialism amongst working men which was still in frequent use until World War Two. Tressell took the name ‘Tressell’ presumably because the trestle was part of the basic equipment of house painters. In the book he spelt the word in different ways, including ‘tressel’ seven times in chapter 47 The Ghouls.

Tressell was full of hope about the book, but he was suffering increasing sickness which in 1910 was reducing him to real poverty. The manuscript, totalling about 250,000 words, had 1,674 quarto pages, plus a title page, a five-page list of 55 chapter numbers and headings, and a five-page preface. It was sub-titled: “Being the story of 12 months in Hell, told by one of the damned, and written down by Robert Tressell.” It was sent to three publishers, who all returned it.

During 1910 Tressell’s failure to find a publisher, his poverty, his unhappy work life and the possibility of better health plus a freer life in Canada, led him to decide to emigrate. He decided he would take Kathleen to Canada and start again, earning good wages and setting up a decent home for Kathleen. He made arrangements to go to Liverpool, where he would get work to help pay for his passage.

Kathleen (then 17) was to move in with her aunt Mary Jane at her school for the blind at 48 Kenilworth Road and 37 Carisbrooke Road (they backed onto each other, near the top of each road), where she would also work. She should have only been there for a few weeks, until Tressell had sorted out the Canada trip, he hoped. They would leave 241 London Road, where they had few possessions. “Not one of his friends seems to have heard a word of his intentions. Perhaps he was diffident about telling them of what must have appeared to them a forlorn hope in his condition.” [Ball 153]

Did he feel he was near the end of his life? Ball and Kathleen thought not, with her saying Tressell “was seemingly ‘well’ at this time and full of hope that it would not be long before we were on the high seas to Canada.” [Ball 155] In August 1910 Tressell went to Liverpool to earn the fare for their trip to Canada. Kathleen watched his train go from Warrior Square Station - and she would never see him again. On the way to Liverpool he may have had trade union help (although Ball could never pin down whether he was a trade union member). [Ball 156-7] In Liverpool he took lodgings at the house of Mr James Johnson, 35 Erskine Street.

Then, on 26 November 1910, Tressell was admitted to Royal Liverpool Infirmary hospital, attached to the workhouse. [Ball 157]

John Nettleton, the Liverpool seaman who in the 1970s spent much time looking into Tressell’s time on Merseyside, said: “So, what can we say about Noonan’s stay in Liverpool? The answer is, very little. The four months of the stay, prior to his admission to the infirmary, are a mixture of mystery, rumour, legend and a few established facts.” [Robert Tressell Lectures 14] Tressell’s sister Ellie lived in Liverpool, but no connection and no descendants were found. There were rumours that Tressell had worked for two specific businesses, but there was no proof of this. Another rumour said he conducted an open-air meeting at the Pier Head. The end came on 3 February 1911. Tressell died at the Hospital of “cardiac arrest due to phthisis or pulmonary tuberculosis” [Robert Tressell Lectures 16] He was 40.

Tuberculosis was then a widespread endemic disease of the urban poor. It is caused by bacterial infection and is most commonly found in the lungs, where it is called pulmonary tuberculosis. Ward said Tressell “slipped out of it all which he had been waiting years to do.” He was buried as a pauper on 10 February, in Walton Park Cemetery, a few yards from Walton Gaol. He was interred in a public grave, number T11 (containing people buried wholly at public expense) with 12 others. It seems no members of the family or anyone else attended the funeral, and the site of the grave was unknown for 60 years. There was no death notice in the Hastings papers and none of his effects were returned to Hastings.

Kathleen said: “I wouldn’t have had him any different except that I wish he had not had so much physical suffering – filled with a burning zeal for justice and the betterment of mankind no matter what the personal cost. He was an agnostic but surely lived the most Christian life I have ever come into contact with, who hated sham and hypocrisy and who loved children and all weak and helpless creatures and who suffered agonies when he contemplated their probable future and his inability to alter them. When he gave way after finishing The RTP he died.” [Ball 161]

Kathleen stayed with the well-off Mary Jane in St Leonards for over two years. She was puzzled why Tressell had left her with a part of the family that disliked him, suspecting he hoped they would support her for shame’s sake. Mary had three daughters and three sons. Kathleen was given board and lodging, but no wages, and her cousins who were there may have been treated the same. The husband, John Bean Meiklejon, lived in London and only visited Hastings for occasional weekends. In 1911 Mary Jane moved her school to 12 Upper Maze Hill.

Kathleen fell in love with her cousin Paul, and they agreed to marry and emigrate to Canada. She first moved to London in the spring of 1913 to become a nurse-governess. Mary was very upset at her leaving, calling her ungrateful. In the summer of 1913 she took another job with Mr and Mrs Mackinlay and their five children in North Finchley. Paul was then in Canada and Kathleen was planning to join him as soon as possible.

Kathleen had the Tressell manuscript, keeping it in a deed-box Tressell had made for it. Mrs Mackinlay saw the box and asked what was inside, and Kathleen told her. “One day Miss Jessie Pope and her friend, who lived next door to the Mackinlays, were having afternoon tea with Mrs Mackinlay and I took the two young boys in to them and was introduced. Mrs Mackinlay had evidently told Miss Pope about the manuscript and she asked to see it and took it away with her. Miss Pope read it and suggested to me that she should show it to Grant Richards.” [Ball 165-6] He was a publisher; his secretary was a cousin of Pope. In her preface to The RTP Pope says “I had chanced upon a remarkable human document.”

Jessie Pope was a professional journalist and possibly a member of the Fabian Society. She had first shown the manuscript to Constables and two other publishers, but they refused it. Richards read the manuscript and told Pope he would publish it if she would cut it down, as it was far too long and repetitious. He then interviewed Kathleen on 22 August 1913 and offered her £25 for all rights. “I was getting £12 a year at Mrs Mackinlay’s and £25 outright seemed a fortune. It was explained to me that it was going to be costly cutting it down to make it possible to publish. Miss Pope probably got more for her work than I did for the manuscript.” [Ball 167]

Ball pointed out that “However ‘generous’ (as Jessie called it) this might have appeared at the time, it was fundamentally unjust to Kathleen and has cast its shadow over the history of The RTP. And furthermore not only did Richards buy all rights of publication for his money but he kept the handwritten manuscript, too, as a property.” [Ball 171]

The Book

The RTP was published for the first time on 23 April 1914, in expurgated form, by Grant Richards Ltd. It cost six shillings, an expensive sum. The author was said to be “Robert Tressall”. Ball found in 1946 that the manuscript was 250,000 words, but only 150,000 were published in 1914. It immediately had many reviews in the national press [Ball 173-6], but none in the local. Then the start of the First World War halted any progress in publishing it.

In June 1914 Kathleen emigrated to Canada and married her cousin Paul Meiklejon – “the first man in my life” [Ball 236] - on 5 July 1914 at Regina, Saskatchewan. They worked as travelling actors until the summer/autumn of 1915. Their daughter Joan was born in Winnipeg on 7 November 1915. But Kathleen grew to dislike Paul and left him in 1918, moving to Toronto, where she worked in a hospital for seven years.

Kathleen and Joan were said by Paul to have been killed in a car accident in 1918, as Paul did not want to admit that she had left him, and the story was believed by all the family. Paul died 1942. Kathleen did not return to England until 1958, then going back to Canada, before coming back to live in England in 1962. But Ball did not find out she was alive until 1967.

In May 1918 Richards published the second, abridged edition of The RTP, with only 90,000 words. But the price was down to one shilling, so sales were much better, and reprints appeared in the 1920s, plus foreign language editions. Critics, however, said it had been toned down. “Most of the sharp and satirical comment upon Christians and employers and general social comment with its strong class feeling has been combed out and the book is centred round the themes of men at work, at home and in recreation, with Robert’s case for socialism represented more by the propaganda sections than by the dramatised scenes of municipal and national politics in action. On the whole, however, this version for all its deficiencies could be said to preserve the spirit of the dead author, though only a pale reflection of it.” [Ball 184]

Fred Ball

There was a breakthrough in spreading the readership of The RTP in April 1940 when Penguin published it for the first time - with its author being “Robert Tressall”. This version claimed to be “complete and unabridged” but was actually only a reprint of the 1918 edition. Nevertheless, by the end of the 1930s the novel had become widely-read and popular, with George Orwell in 1940 describing it as “A wonderful book”. [Harker 138]

But The RTP only became the highly influential post-war political force that it was because of its publication in full in 1955 - thanks to Fred Ball.

Ball had read it for the first time in 1936 when he was lent a copy by a friend who was a house-painter. Ball was intrigued to discover that the moving story of hardship, unfairness and civic corruption was set in his home town of Hastings, so he tried to find out more about Tressell but was initially unsuccessful. Then in November 1942 he had a letter published in the Hastings Observer, saying he was “preparing a short biography” of Tressell and asking for any information, and then in other newspapers. [Ball x and Observer, 7 November 1940]

Ball was born in Hastings Old Town on 1 March 1905. His father was a gardener and his mother a seamstress at Plummer Roddis, the town’s biggest drapers (now Debenhams). In 1908 Fred’s father became a gardener at Telham, between Hastings and Battle, and the family moved there. Fred went to school in Battle until 1919, and then had a series of jobs (including as a counterhand at a branch of Sainsbury’s in London) before returning to Hastings in 1933. [Harker 130-1]

Before and after the Second World War Fred lived at 27 Edmund Road, an attractive semi-detached house in Clive Vale. He continued having a varied working life while he researched Tressell and wrote his own books and poems. He became quite well-known locally as a meter reader for the Gas Company, and his last job was as a bookmaker’s clerk, before retiring in 1966. Fred was a member in turn of high, low and spiritualist churches, and later joined the Communist Party. The books he wrote included A Breath of Fresh Air and A Grotto for Miss Maynier, and he also produced much poetry, saying late in life “I always wanted to be an English poet above all things, a pastoral poet”. [Observer, 28 February 1985] He died on 14 April 1988, when living at Fearon Road, Blacklands, leaving a wife, Jackie, and four daughters. Jackie recalled: “He used to write in longhand and I typed all the books”. [Observer, 21 April 1988; also 28 February 1985]

Towards the end of the Second World War Ball decided to try and obtain the manuscript of The RTP and publish in full. The manuscript was then owned by a Mr Robert Partridge, who, after lengthy negotiation, agreed to sell it for 60 guineas (£63) to Ball and a small group of friends (Peter Blackman, George Jackson, Ernie Bevis, Gregory Gildersleeve and Mr and Mrs Andrew Kelt). The 1914 publisher Grant Richards, when about to retire in financial difficulties, had given the manuscript to his secretary Pauline Hemmerde as a reward for her lifetime’s devotion. She had sold it for £10 to a stranger, presumably Partridge. On 29 September 1946 Ball and Andrew Kelt met Partridge at the Elephant and Castle underground station, and the three then went to “a sort of transport cafe over the road”. [WEA 19]. The manuscript, in two parcels, was opened on the cafe table, and they spent an hour talking about it over two cups of tea each.

Ball then found that 40% of the manuscript – 100,000 words – had been cut from the 1914 edition and “as much as 160,000” from the 1918 abridged edition. The smaller of the two parcels contained the material cut out by Grant Richards. Ball tried to persuade several publishers to produce the complete book, but this was thwarted by Richards Press owning the copyright, and themselves not wanting to publish it in full. They would have to be paid royalties until 1964.

Ball carried on collecting a large quantity of material about both Tressell and Edwardian Hastings, and was not deterred by events such as George Bernard Shaw in 1948 saying in reply to a letter from Ball: “I never heard of Robert Tressell and am not interested in him.” [Ball 186]

The first biography of Tressell by Fred Ball, Tressell of Mugsborough, was published in October 1951 by Lawrence and Wishart. This described for the first time who Tressell was, and helped turn him into a national socialist hero. The book received good reviews, and prompted widespread support for Ball’s attempts to publish The RTP complete.

The Book in Full

But Richards Press still owned the copyright and initially only suggested they would simply publish separately the parts that had been cut out. Eventually, however, they agreed that Lawrence and Wishart could publish the novel in full, for the first time. This took place on 5 October 1955. The first print was 5,000, with 1,500 in the hard cover library edition at 30/-, and 3,500 in cloth as a trade union edition at 10/6. All were sold in three months. The Manchester Evening News called it “the only real working class novel”. [Harker 175]

In August 1958 Ball and the shareholders sold the manuscript to the National Federation of Building Trades Operatives for £130. Ball and his wife Jacqueline took the manuscript to the Federation’s head office in Clapham packed in a box marked “Processed Peas”. In January 1959 the Federation handed it over to the TUC, at a simple ceremony, and since then it has been in the TUC library.

On 2 June 1962 a seat in memory of Tressell, in Carlisle Parade, was presented to the town by trade union leaders, and a temporary memorial plaque at 115 Milward Road was unveiled. This had been provided by the Trades Council, who in 1964 replaced it with the plaque made of marble which is still in place.